Statistics and data analysis

General informations

Organization

| S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lectures | 8 (12h) | 8 (12h) | 8 (12h) | 8 (12h) |

| Tutorials | 8 (12h) | 8 (12h) | 8 (12h) | 8 (12h) |

| tot. | 16 (24h) | 16 (24h) | 16 (24h) | 16 (24h) |

- Lectures : no need to bring your personal computer

- Tutorials : bring your personal computer

https://ant0in3g.github.io/sTa7.html \(\to\) look at your stickers !

Evaluations and Group projets

Evaluations

For each semester :

- One mid-semester exam (1h30)

- One final exam (1h30)

Group projets

Semester 2 :

Semester 4 :

Semester 6 :

Resources and OneDrive folder

Resources

Cours complet de Statistiques et analyse de données (en construction)

An Introduction to Statistical Learning from the Stanford University with a YouTube playlist of the lectures

Shared OneDrive folder

A OneDrive folder has been shared with every student

Introduction to statistics and/with R

- Data : interesting

\(\to\) they help us understand the world !

- Statistics : fundamental in science

\(\to\) needed in the design, analysis, and interpretation of experiments !

![]() A brief intro to R and RStudio

A brief intro to R and RStudio

- Free open source language

- Built to do statistics

- Updated by the mathematician from all over the world

- Amazing graphics !

- Widely used in biology, agronomy, economy, …

R and RStudio

Learn it, love it, use it !

Installation of R and RStudio

To Do !

Install R and RStudio for next class !

Basics of R and RStudio

A very great video to learn the basics of R

Good habits

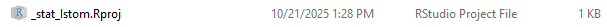

- create a project on RStudio

- create ALWAYS 4 folders :

data_rawdataimgdoc

- Use the

helpfunction ! … and alsochat GPT…

WARNING ! It often writes code wayyyy too complicated ! - What you see in your OneDrive folder :

Launch RStudio

Always launch your RStudio project with

Using RStudio

Import DATA into RStudio

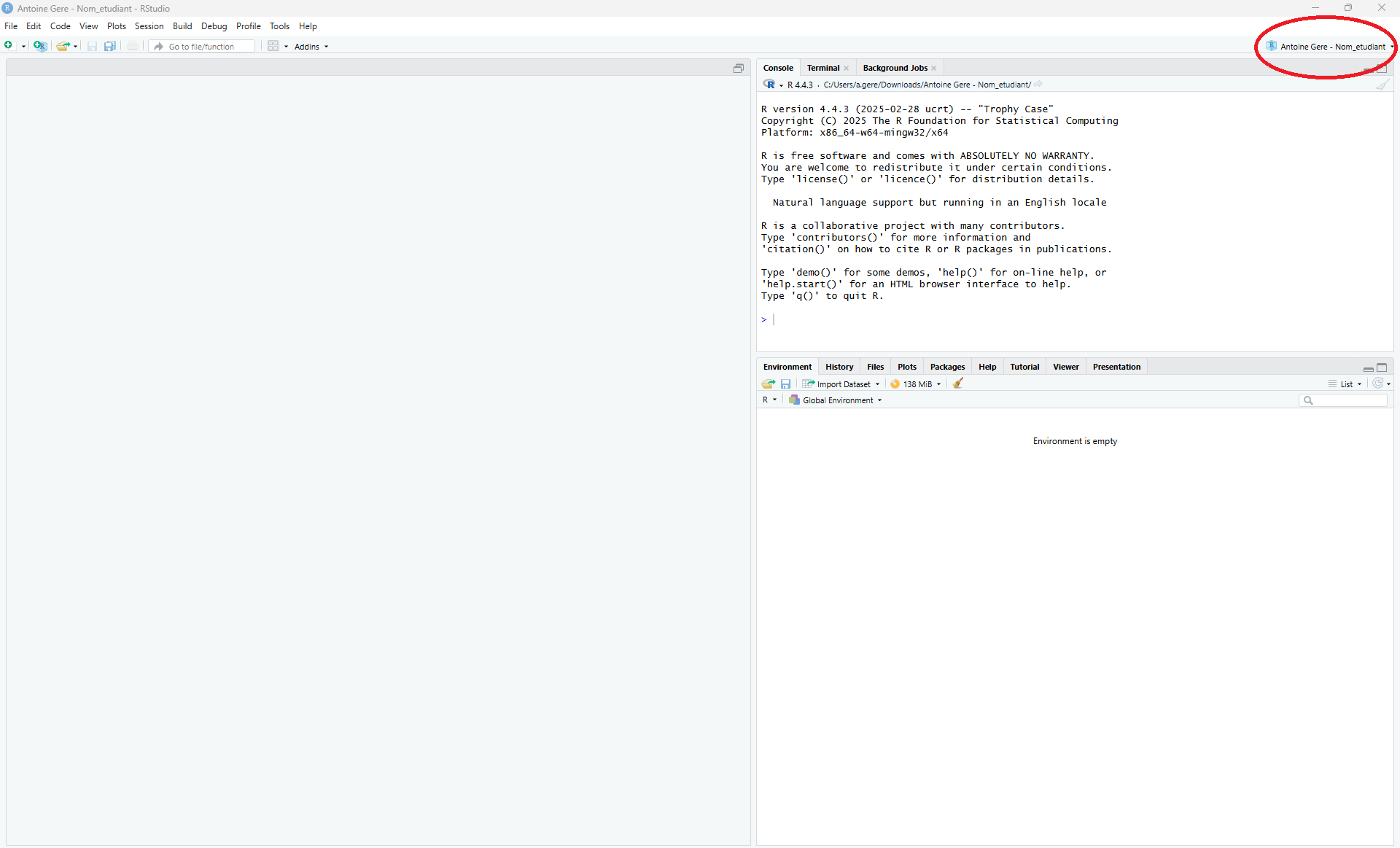

- Data used for this class :

Data.Lecture.xlsx

Important

You can download it by clicking on Data.Lecture.xlsx !

- Import data from an excel file

- Possible to import data from many more file formats …

Let’s get started

NOW “doing statistics” can get started !

![]() Exploring data

Exploring data

Def.

- A variable \(X\) is any characteristic observed in a study.

- The data values that we observe for a variable are called observations

Qualitative / Categorical Variable

A variable is called qualitative if each observation belongs to a set of distinct categories

Nominal : Categories are disconnected. (Examples : Hair Color, Animal Species, …)

Ordinal : Categories are ranked (Example : Level of Education, …)

Quantitative / Numerical Variable

A variable is called quantitative if observations on it take numerical values that represent different magnitudes of the variable

Discrete : the variable assume values in a countable set (Examples : Number of episode in a series, Grades, …)

Continuous : the variable assume values in a continuous set (Examples : Time, most physical measurements, …)

In a dataset (sample of a population) we have measurements of variables for different individuals.

- Unit / individual : A member of a population

- Population : The collection of all individuals / units that we want to know more about

- Sample : The subset of the population we observe

- Modality : The distinct values or categories that the variable can take

Before making advanced statistics with our data it is essential to examine all our variables !

Why ? To “listen” to the data :

- to catch mistakes

- to see patterns in the data

- to find violations of statistical assumptions

- to generate hypotheses

- … and because if you don’t, you will have trouble later !

- We will recall notions of descriptive Statistics with R

- This has been written using this webpage (INRAE)

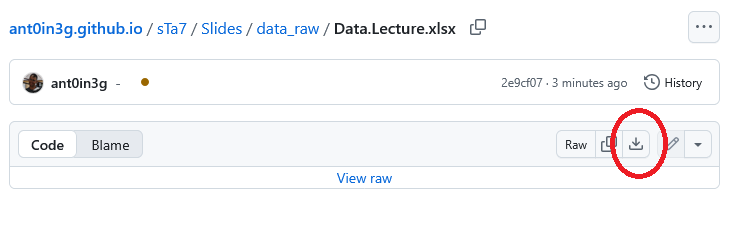

We will use the dataset iris.

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa[1] 150 5There are 5 variables and 150 individuals.

4 quantitative variables :

Sepal.LengthSepal.Width

Petal.Length

Petal.Width

1 qualitative variable :

Species

![]() Univariate statistics

Univariate statistics

To have a global view : summary

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Min. :4.300 Min. :2.000 Min. :1.000 Min. :0.100

1st Qu.:5.100 1st Qu.:2.800 1st Qu.:1.600 1st Qu.:0.300

Median :5.800 Median :3.000 Median :4.350 Median :1.300

Mean :5.843 Mean :3.057 Mean :3.758 Mean :1.199

3rd Qu.:6.400 3rd Qu.:3.300 3rd Qu.:5.100 3rd Qu.:1.800

Max. :7.900 Max. :4.400 Max. :6.900 Max. :2.500

Species

setosa :50

versicolor:50

virginica :50

The command summary gives us :

- for the quantitative variables :

- the minimum

- the 1st quartile

- the median

- the mean

- the 3rd quartile

- the maximum

- for the qualitative variables :

- the number of observations in each category

Using describe for data summaries :

iris

5 Variables 150 Observations

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sepal.Length

n missing distinct Info Mean pMedian Gmd .05

150 0 35 0.998 5.843 5.8 0.9462 4.600

.10 .25 .50 .75 .90 .95

4.800 5.100 5.800 6.400 6.900 7.255

lowest : 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7, highest: 7.3 7.4 7.6 7.7 7.9

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sepal.Width

n missing distinct Info Mean pMedian Gmd .05

150 0 23 0.992 3.057 3.05 0.4872 2.345

.10 .25 .50 .75 .90 .95

2.500 2.800 3.000 3.300 3.610 3.800

lowest : 2 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5, highest: 3.9 4 4.1 4.2 4.4

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Petal.Length

n missing distinct Info Mean pMedian Gmd .05

150 0 43 0.998 3.758 3.65 1.979 1.30

.10 .25 .50 .75 .90 .95

1.40 1.60 4.35 5.10 5.80 6.10

lowest : 1 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4, highest: 6.3 6.4 6.6 6.7 6.9

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Petal.Width

n missing distinct Info Mean pMedian Gmd .05

150 0 22 0.99 1.199 1.2 0.8676 0.2

.10 .25 .50 .75 .90 .95

0.2 0.3 1.3 1.8 2.2 2.3

lowest : 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5, highest: 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Species

n missing distinct

150 0 3

Value setosa versicolor virginica

Frequency 50 50 50

Proportion 0.333 0.333 0.333

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The

Hmiscpackage provides thedescribefunction to quickly summarize a dataset.

- For quantitative variables, it reports :

- number of observations

- missing values

- mean

- quantiles (5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 95%)

- 5 lowest and 5 highest values

- For qualitative variables, it reports :

- number of observations

- missing values

- number of modalities

- frequency and proportion of each modality

Quantitative variables

For each quantitative variable, it is also possible to obtain the following statistics separately.

- the sum of all the modalities in

Sepal.Length

- the mean of the variable

Sepal.Length

- the variance of the variable

Sepal.Length

- the standard deviation of the variable

Sepal.Length

- the minimum of the variable

Sepal.Length

- the maximum of the variable

Sepal.Length

- the median of the variable

Sepal.Length

- the quantiles of the variable

Sepal.Length

- the number of modalities in the variable

Sepal.Length

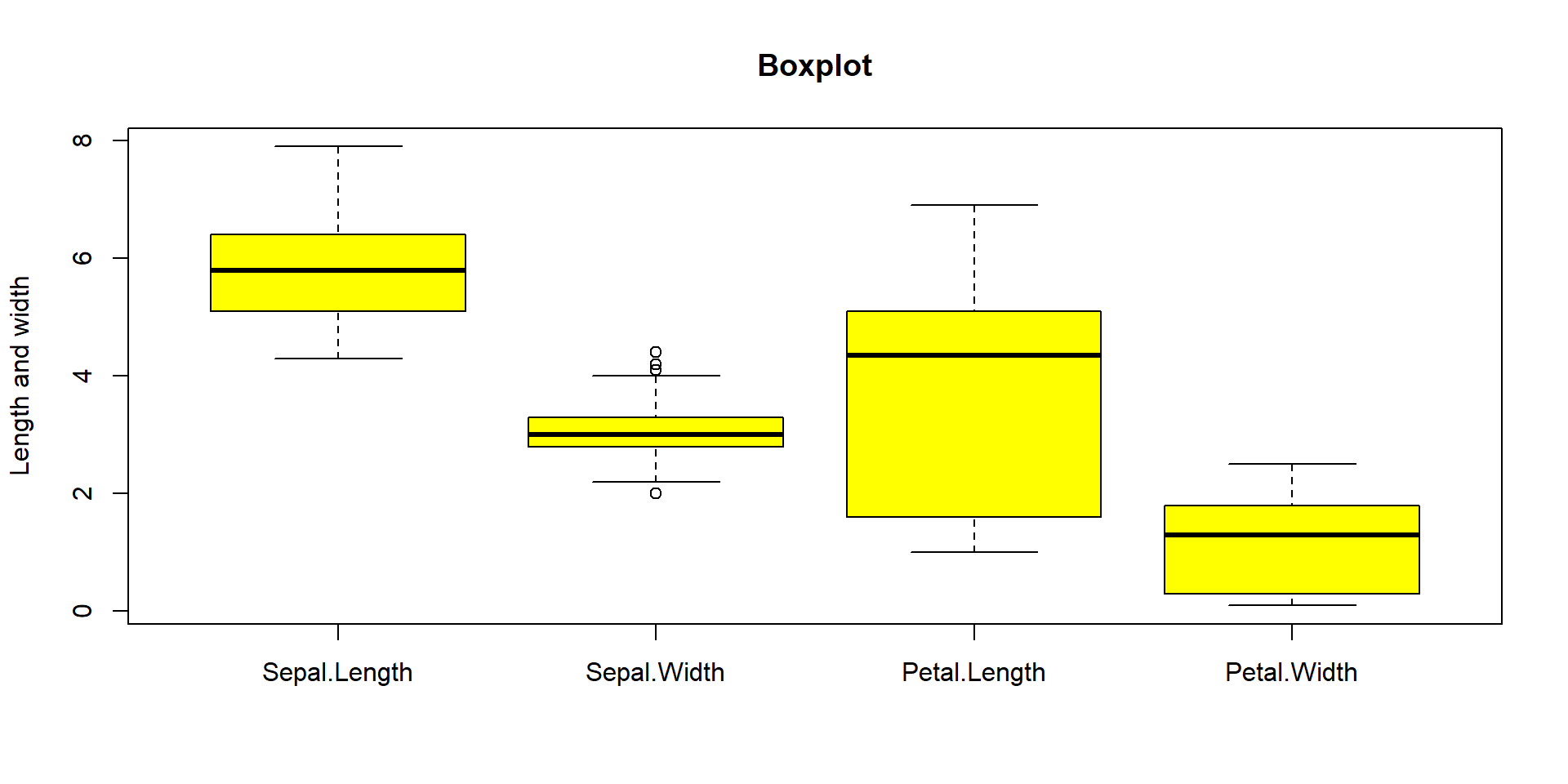

Chart representations

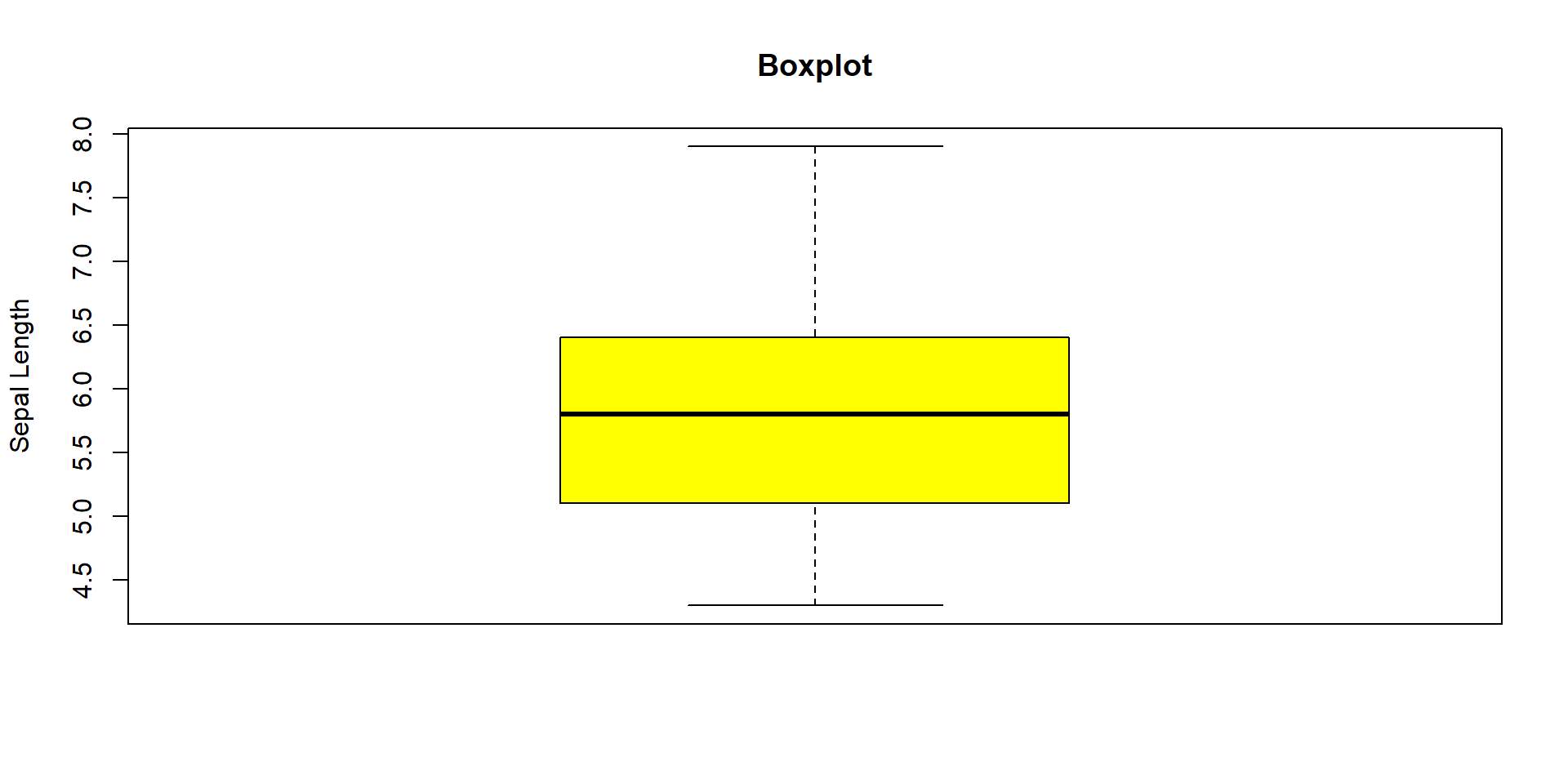

- A first representation is to use a boxplot

- Graphical way to summarize a quantitative variable

- Show its distribution, central tendency, and spread, including outliers.

Components of a Boxplot :

- Median (Q2)

- The line inside the box represents the median — the middle value of the data.

- It divides the data into two equal sets.

- The line inside the box represents the median — the middle value of the data.

- Quartiles (Q1 and Q3)

- Q1 (bottom of the box): 25% of the data is below this value.

- Q3 (top of the box): 75% of the data is below this value.

- The box shows the interquartile range (IQR = Q3 − Q1), which contains the middle 50% of the data.

- Q1 (bottom of the box): 25% of the data is below this value.

- Whiskers

- Lines extending from the box to the minimum and maximum values within a certain range (usually 1.5 × IQR from Q1 and Q3)

- Outliers

- Points outside the whiskers plotted individually.

- Represent values that are unusually high or low compared to the rest of the data.

- Points outside the whiskers plotted individually.

Also possible to represent many boxplot on the same plot

boxplot(iris[,c('Sepal.Length','Sepal.Width','Petal.Length','Petal.Width')],

col = c("yellow"), #Pour la couleur

main = paste("Boxplot"), #Pour le titre

ylab = "Length and width") #Pour le titre de l’axe des ordonnées

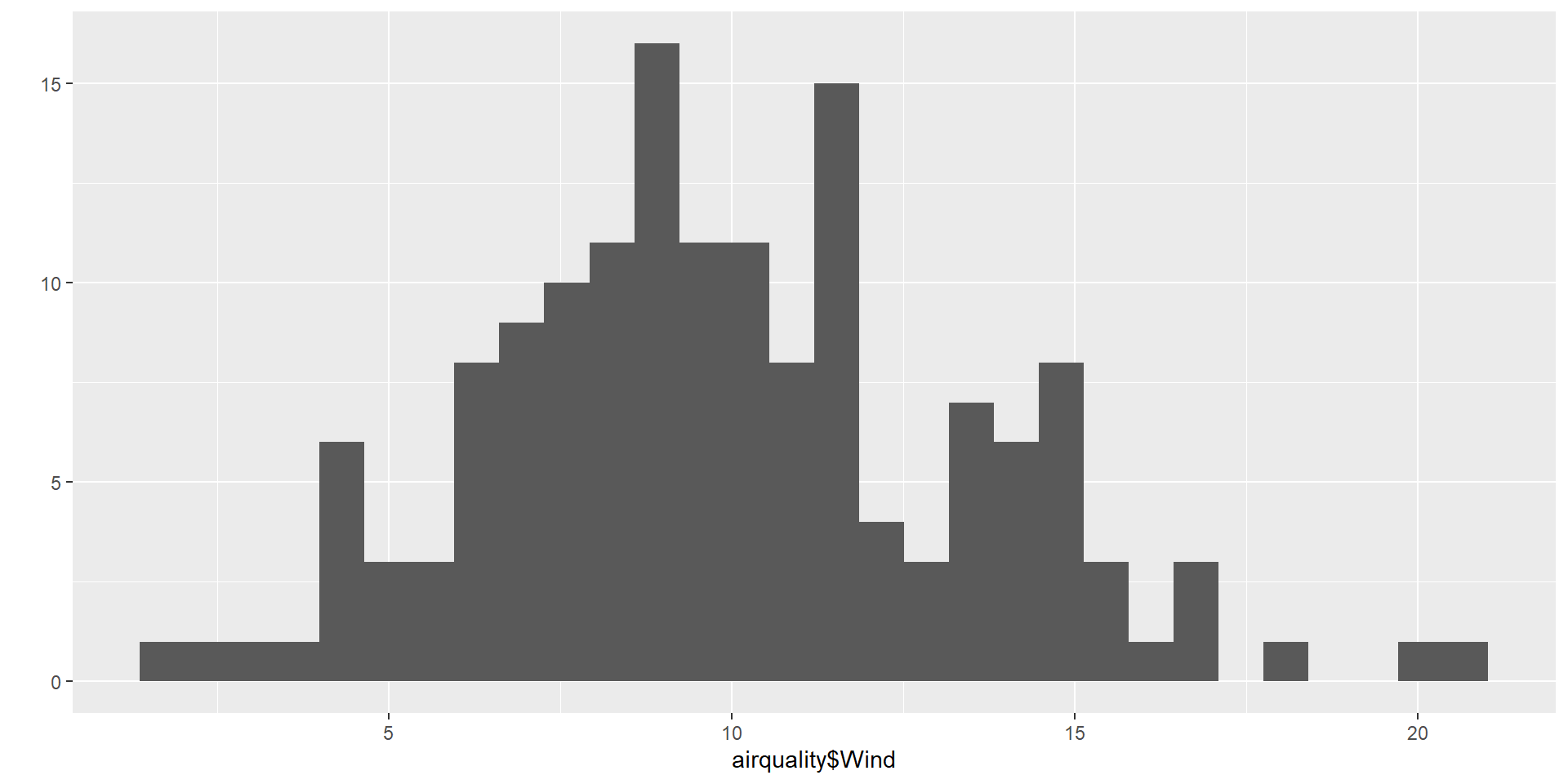

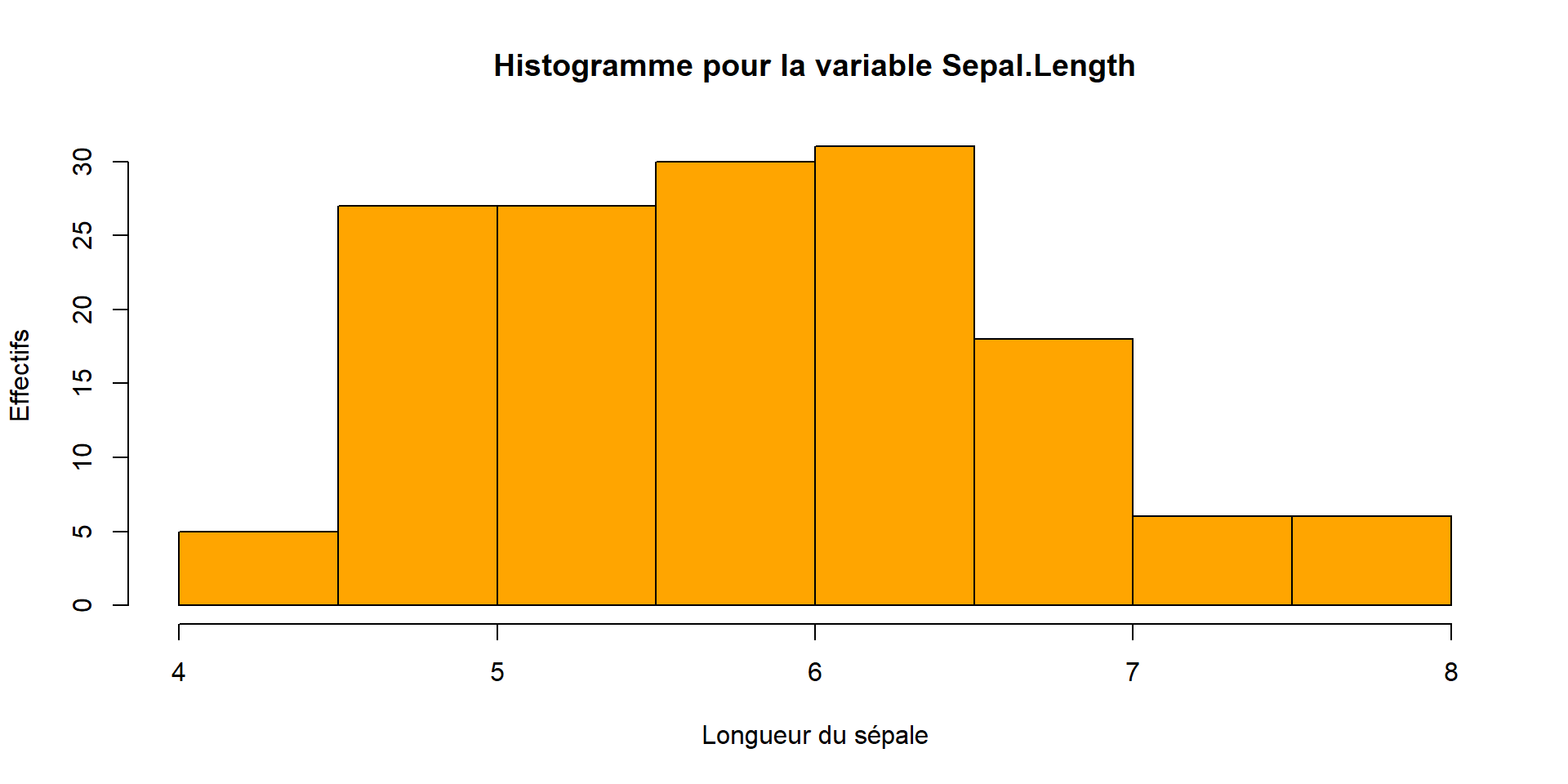

A usual graph is the histogram. It is a type of bar graph that represents the distribution of a quantitative variable.

Key Features

Bins (Intervals):

The x-axis is divided into continuous intervals called bins, each representing a range of values.Frequency:

The y-axis shows the number of observations (frequency) in each bin.Bars:

Each bin is represented by a bar.

The height of the bar corresponds to the frequency.

Bars touch each other because the data is continuous.Distribution Shape:

A histogram helps visualize the shape of the data:- Symmetric or skewed

- Uniform (flat)

- Bimodal (two peaks)

- Unimodal (one peak)

- Symmetric or skewed

Why using an histogram ?

- Understand the shape of the data.

- Detect patterns, skewness, or clusters.

- Identify outliers or unusual gaps.

hist(iris$Sepal.Length,

col = c("orange"),

main = paste("Histogramme pour la variable Sepal.Length"),

ylab = "Effectifs",

xlab = "Longueur du sépale")

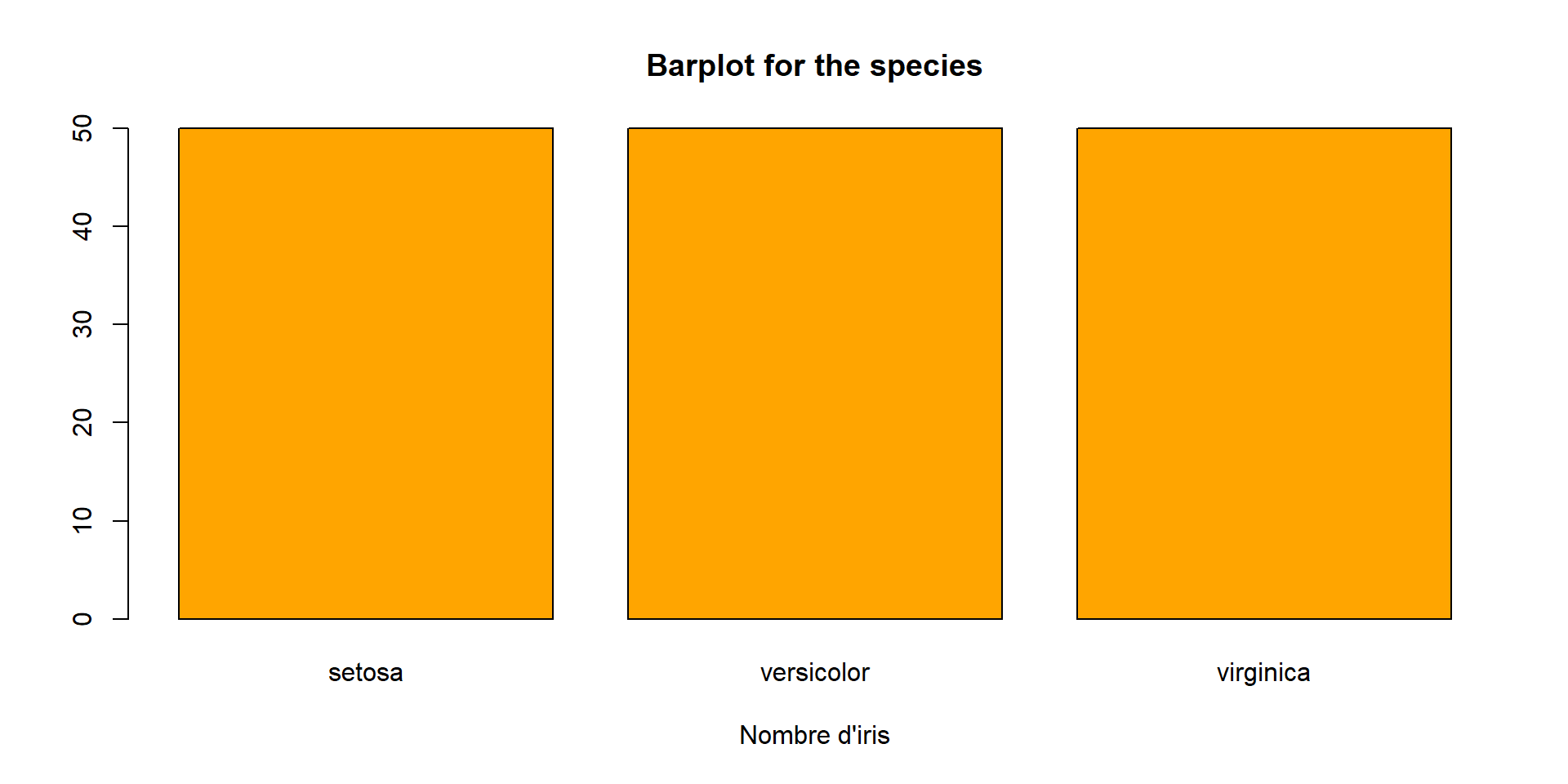

Qualitative variables

- the command

tablesummarize categorical data by counting the frequency of each unique value - It creates a contingency table, which is very useful in statistics for understanding distributions

The same with the proportions :

and finally we can draw the bar plot for this variable

![]() Bivariate statistics

Bivariate statistics

- Summarize and describe the relationship between two variables

- Explore how one variable changes with respect to another

Three types of situations :

- Quantitative – Quantitative : Both variables are numeric

- Quantitative – Qualitative : One numeric, one categorical

- Qualitative – Qualitative : Both categorical

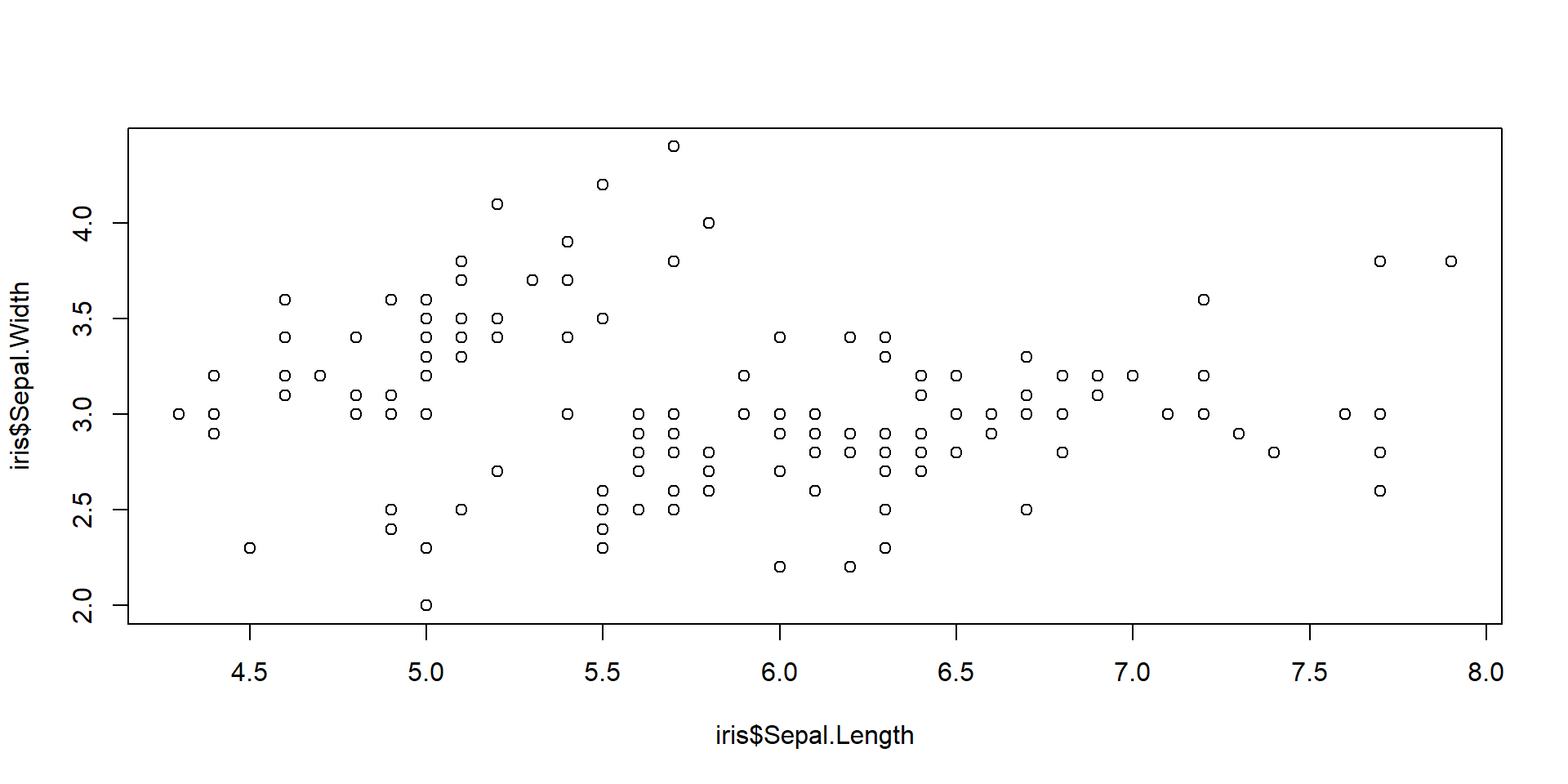

Quantitative VS Quantitative

A scatter plot is one of the most commonly used tools to visualize the relationship between two quantitative variables.

It can give an idea of the relationship between the 2 variables.

Quantitative VS Qualitative

The command by gives statistics summary for each modality of the qualitative variable

iris[, "Species"]: setosa

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Min. :4.300 Min. :2.300 Min. :1.000 Min. :0.100

1st Qu.:4.800 1st Qu.:3.200 1st Qu.:1.400 1st Qu.:0.200

Median :5.000 Median :3.400 Median :1.500 Median :0.200

Mean :5.006 Mean :3.428 Mean :1.462 Mean :0.246

3rd Qu.:5.200 3rd Qu.:3.675 3rd Qu.:1.575 3rd Qu.:0.300

Max. :5.800 Max. :4.400 Max. :1.900 Max. :0.600

------------------------------------------------------------

iris[, "Species"]: versicolor

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Min. :4.900 Min. :2.000 Min. :3.00 Min. :1.000

1st Qu.:5.600 1st Qu.:2.525 1st Qu.:4.00 1st Qu.:1.200

Median :5.900 Median :2.800 Median :4.35 Median :1.300

Mean :5.936 Mean :2.770 Mean :4.26 Mean :1.326

3rd Qu.:6.300 3rd Qu.:3.000 3rd Qu.:4.60 3rd Qu.:1.500

Max. :7.000 Max. :3.400 Max. :5.10 Max. :1.800

------------------------------------------------------------

iris[, "Species"]: virginica

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

Min. :4.900 Min. :2.200 Min. :4.500 Min. :1.400

1st Qu.:6.225 1st Qu.:2.800 1st Qu.:5.100 1st Qu.:1.800

Median :6.500 Median :3.000 Median :5.550 Median :2.000

Mean :6.588 Mean :2.974 Mean :5.552 Mean :2.026

3rd Qu.:6.900 3rd Qu.:3.175 3rd Qu.:5.875 3rd Qu.:2.300

Max. :7.900 Max. :3.800 Max. :6.900 Max. :2.500 The psych package, using describe, allows to compute the following statistics :

Number of observations

Mean

Standard deviation

Median

Trimmed mean (calculated by removing the 5 smallest and 5 largest values)

Median absolute deviation (robust measure of spread, defined as the median of the absolute differences between each value and the dataset’s median)

Minimum

Maximum

Range (maximum − minimum)

Skewness (measures the asymmetry of a distribution, indicating whether the data are skewed to the left (negative) or right (positive) )

Kurtosis (measures the “tailedness” of a distribution, indicating whether data have heavy tails (outliers) or light tails compared to a normal distribution)

Standard error (measures how much a sample mean is likely to vary from the true population mean)

Descriptive statistics by group

group: setosa

vars n mean sd median trimmed mad min max range skew kurtosis

Sepal.Length 1 50 5.01 0.35 5.0 5.00 0.30 4.3 5.8 1.5 0.11 -0.45

Sepal.Width 2 50 3.43 0.38 3.4 3.42 0.37 2.3 4.4 2.1 0.04 0.60

Petal.Length 3 50 1.46 0.17 1.5 1.46 0.15 1.0 1.9 0.9 0.10 0.65

Petal.Width 4 50 0.25 0.11 0.2 0.24 0.00 0.1 0.6 0.5 1.18 1.26

Species 5 50 1.00 0.00 1.0 1.00 0.00 1.0 1.0 0.0 NaN NaN

se

Sepal.Length 0.05

Sepal.Width 0.05

Petal.Length 0.02

Petal.Width 0.01

Species 0.00

------------------------------------------------------------

group: versicolor

vars n mean sd median trimmed mad min max range skew kurtosis

Sepal.Length 1 50 5.94 0.52 5.90 5.94 0.52 4.9 7.0 2.1 0.10 -0.69

Sepal.Width 2 50 2.77 0.31 2.80 2.78 0.30 2.0 3.4 1.4 -0.34 -0.55

Petal.Length 3 50 4.26 0.47 4.35 4.29 0.52 3.0 5.1 2.1 -0.57 -0.19

Petal.Width 4 50 1.33 0.20 1.30 1.32 0.22 1.0 1.8 0.8 -0.03 -0.59

Species 5 50 2.00 0.00 2.00 2.00 0.00 2.0 2.0 0.0 NaN NaN

se

Sepal.Length 0.07

Sepal.Width 0.04

Petal.Length 0.07

Petal.Width 0.03

Species 0.00

------------------------------------------------------------

group: virginica

vars n mean sd median trimmed mad min max range skew kurtosis

Sepal.Length 1 50 6.59 0.64 6.50 6.57 0.59 4.9 7.9 3.0 0.11 -0.20

Sepal.Width 2 50 2.97 0.32 3.00 2.96 0.30 2.2 3.8 1.6 0.34 0.38

Petal.Length 3 50 5.55 0.55 5.55 5.51 0.67 4.5 6.9 2.4 0.52 -0.37

Petal.Width 4 50 2.03 0.27 2.00 2.03 0.30 1.4 2.5 1.1 -0.12 -0.75

Species 5 50 3.00 0.00 3.00 3.00 0.00 3.0 3.0 0.0 NaN NaN

se

Sepal.Length 0.09

Sepal.Width 0.05

Petal.Length 0.08

Petal.Width 0.04

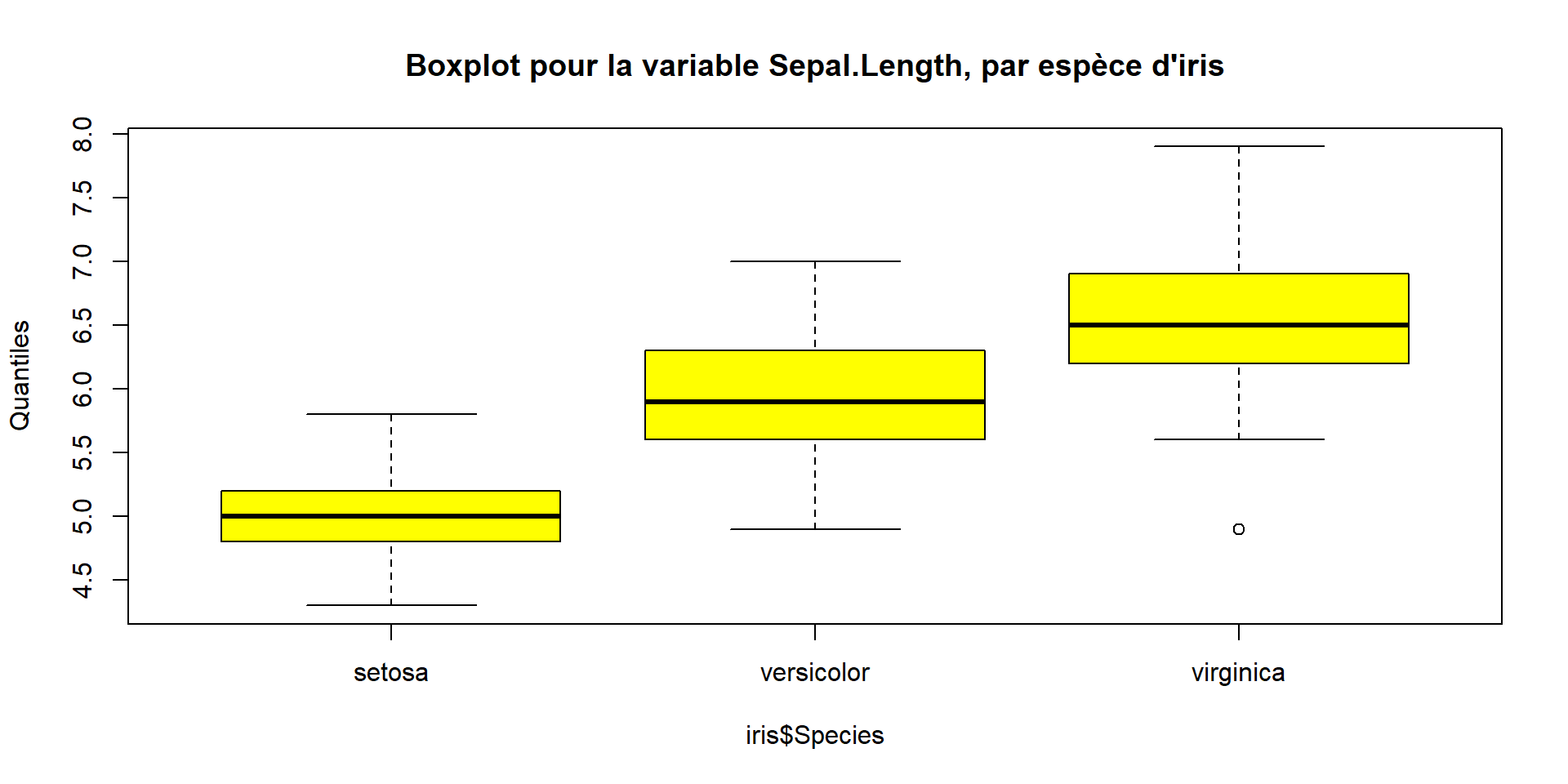

Species 0.00For each quantitative variable, possible to plot the boxplot for all the modalities of the qualitative variable.

boxplot(iris$Sepal.Length ~ iris$Species,

col = c("yellow"),

main = paste("Boxplot pour la variable Sepal.Length, par espèce d'iris"),

ylab = "Quantiles")

Qualitative VS Qualitative

First we create another qualitative variable for our example : Sepal.Length_cat

Now we have

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species Sepal.Length_cat

1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa moyen

2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa petit

3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa petit

4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa petit

5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa petit

6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa moyenWe get contingency table with table

grand moyen petit

setosa 0 22 28

versicolor 20 27 3

virginica 41 8 1the sum for each modality of Species

the sum for each modality of Sepal.Length_cat

the same with proportions (with respect to the total number of observations)

grand moyen petit

setosa 0.000000000 0.146666667 0.186666667

versicolor 0.133333333 0.180000000 0.020000000

virginica 0.273333333 0.053333333 0.006666667now with respect to the number of observations for each row

grand moyen petit

setosa 0.00 0.44 0.56

versicolor 0.40 0.54 0.06

virginica 0.82 0.16 0.02and finally with respect to the number of each column

grand moyen petit

setosa 0.0000000 0.3859649 0.8750000

versicolor 0.3278689 0.4736842 0.0937500

virginica 0.6721311 0.1403509 0.0312500The gmodels package allows to create more advanced tables.

library(gmodels)

CrossTable(iris$Species,iris$Sepal.Length_cat,prop.chisq=FALSE,chisq=FALSE,expected=FALSE)

Cell Contents

|-------------------------|

| N |

| N / Row Total |

| N / Col Total |

| N / Table Total |

|-------------------------|

Total Observations in Table: 150

| iris$Sepal.Length_cat

iris$Species | grand | moyen | petit | Row Total |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

setosa | 0 | 22 | 28 | 50 |

| 0.000 | 0.440 | 0.560 | 0.333 |

| 0.000 | 0.386 | 0.875 | |

| 0.000 | 0.147 | 0.187 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

versicolor | 20 | 27 | 3 | 50 |

| 0.400 | 0.540 | 0.060 | 0.333 |

| 0.328 | 0.474 | 0.094 | |

| 0.133 | 0.180 | 0.020 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

virginica | 41 | 8 | 1 | 50 |

| 0.820 | 0.160 | 0.020 | 0.333 |

| 0.672 | 0.140 | 0.031 | |

| 0.273 | 0.053 | 0.007 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Column Total | 61 | 57 | 32 | 150 |

| 0.407 | 0.380 | 0.213 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Probability and sampling

coming !

![]() Probability

Probability

coming !

![]() Sampling

Sampling

coming !

Statistical tests

- Tools to decide if data supports an hypothesis

- Compare observed results with what is expected under an hypothesis

- Help control errors

- Guide data-driven decisions

![]() Statistical hypothesis tests

Statistical hypothesis tests

A procedure to know if something has changed in a poputalion.

- Collect a sample that is representative of the whole population.

- State the hypothesis you want to test.

A very good video about statistical hypothesis testing.

The Hypothesis

Two Competing Hypotheses :

Null hypothesis H0 :

The conservative hypothesis ; “There is nothing going on !”Alternative hypothesis H1 :

“There is something going on”

Type 1 and Type 2 Errors

In a hypothesis test, we make a decision about which of H0 or H1 might be true, but our decision might be incorrect !

| We fail to reject \(H_0\) | We reject \(H_0\) | |

|---|---|---|

| In reality \(H_0\) is true | \(\checkmark\) | Type 1 Error \(\alpha\) |

| In reality \(H_1\) is true | Type 2 Error \(\beta\) | \(\checkmark\) |

- Goal : Minimizing Type I error (\(\alpha\)) and Type II error \((\beta)\)

- Many ways to minimize a problem with 2 parameters.

Type I error > Type II error

Type I error (\(\alpha\)) and Type II error \((\beta)\) DO NOT HAVE THE SAME IMPACT on the situation being tested !!

Type I error (\(\alpha\)) is way more harmful !

Therefore we fix \(\alpha\) as small as we like, and try to minimize \(\beta\).

“Inside” a statistical hypothesis test

Important

The next step of hypothesis testing is to weigh the evidence !

Could these data plausibly have happened by chance if the H0 was true ?

The procedure :

We collect data in our population

We import our data in RStudio

We use the right test

We “write” the test we chose

And according to the p-value we get, we can accept or reject H0

- If p-value > \(\alpha\), then we accept H0

- If p-value < \(\alpha\), then we reject H0

What remains to be learned?

We now need to learn which test to choose, how to choose it, and how to implement it on RStudio.

cf. next slides

Example

A first example of hypothesis testing within R.

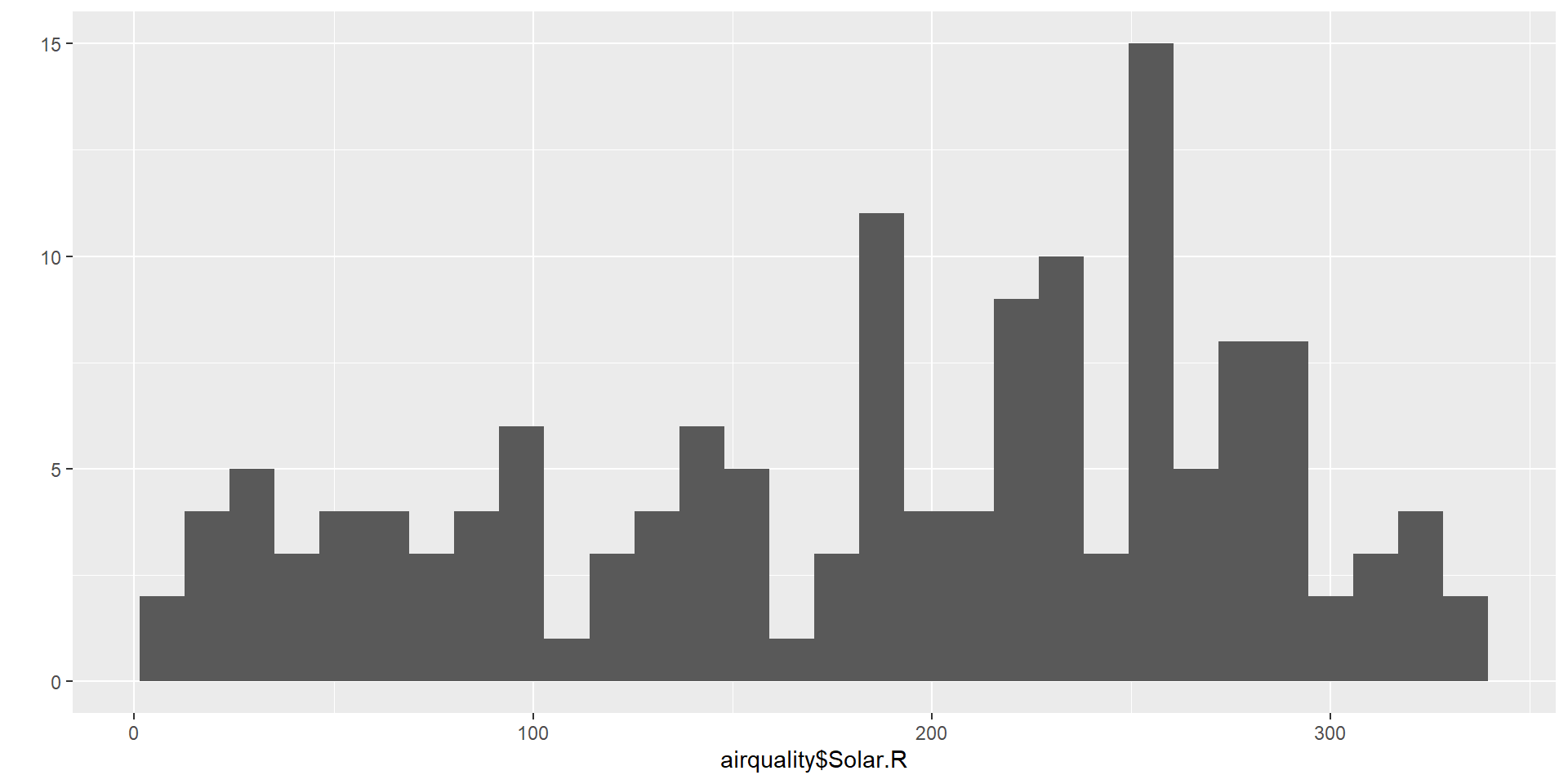

In this video, the author tackle two questions relating to R’s built-in airquality data set. We’ll view this set as a simple random sample of air quality measurements in New York City.

Questions

- An official claims that the average wind speed in the city is 9 miles per hour. Is this plausible ?

- A certain solar array will only be cost-effective if mean solar radiation is over 175 Langleys. Would it be a sound investment in light of this data?

Let’s go work on RStudio.

Ozone Solar.R Wind Temp Month Day

1 41 190 7.4 67 5 1

2 36 118 8.0 72 5 2

3 12 149 12.6 74 5 3

4 18 313 11.5 62 5 4

5 NA NA 14.3 56 5 5

6 28 NA 14.9 66 5 6[1] 153 6The dataset used here is called airquality. There are 6 variables and 153 individuals.

Ozone

Solar.R

Wind

TempMonth

Day

Question 1

In order to answer the first question, we look at Wind

H0 : the null hypotesis

Here the null hypotesis is that the average wind speed in the city is 9 miles per hour.

We will use here a t.test. We explain more about this test in next slides.

One Sample t-test

data: airquality$Wind

t = 3.3619, df = 152, p-value = 0.0009794

alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 9

95 percent confidence interval:

9.394804 10.520229

sample estimates:

mean of x

9.957516 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.0010 \ \simeq \ 0.1 \% \ < \alpha = 5 \%\)

Conclusion

We can therefore reject H0.

The average wind speed in the city is NOT 9 miles per hour.

Question 2

In order to answer the second question, we look at Solar.R

H0 : the null hypotesis

Here the null hypotesis is that the mean solar radiation is 175 Langleys.

And the alternative hypothesis H1 is that this mean is greater than 175 Langleys.

Again we will use here a t.test.

One Sample t-test

data: airquality$Solar.R

t = 1.4667, df = 145, p-value = 0.07232

alternative hypothesis: true mean is greater than 175

95 percent confidence interval:

173.5931 Inf

sample estimates:

mean of x

185.9315 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.072 \ \simeq \ 7.2 \% \ > \alpha = 5 \%\)

Conclusion

We can therefore accept H0.

![]() Parametric and nonparametric statistical tests

Parametric and nonparametric statistical tests

Parametric tests : requirements about the shape of the populations involved

Non-parametric tests do not require that samples come from populations with normal distributions or have any other particular distributions.

Non-parametric tests are called distribution-free tests.

An interesting on the difference between parametric and non-parametric test.

Parametric tests < Non-parametric tests

Nonparametric methods can be applied to a wide variety of situations because they do not have the more rigid requirements of the corresponding parametric methods.

Unlike parametric methods, nonparametric methods can often be applied to categorical data.

Nonparametric methods usually involve simpler computations than the corresponding parametric methods.

Parametric tests > Non-parametric tests

Nonparametric methods tend to waste information

Nonparametric tests are not as efficient as parametric tests

With a nonparametric test we need stronger evidence (such as a larger sample or greater differences) before we reject a null hypothesis.

![]() Chi-squared tests

Chi-squared tests

There are three types of Chi-squared tests.

We write Chi-squared OR \(\chi^2\).

![]() \(\chi^2\) goodness-of-fit test

\(\chi^2\) goodness-of-fit test

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | / |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitative |

Asumption :

- Observations must be independent

H0 : Null hypothesis

The population follows the specified distribution.

Example :

The author tackle two goodness-of-fit problems using R.

- One with different proportions

- One with same proportions

1st problem

- A college reports that

- \(50 \%\) of the students in its statistics classes are freshmen,

- \(30 \%\) are sophomores,

- \(10 \%\) are juniors,

- and \(10 \%\) are seniors.

A simple random sample of \(65\) such students has the following breakdown :

| Freshman | Sophomore | Junior | Senior |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 24 | 9 | 4 |

Question

Does this constitute sufficient evidence to doubt the percentages reported by the college ?

We define the variable years sample

then the proportions expected from what the college did report

Now we can perform our goodness-of-fit test.

Here the null hypothesis is that the population follows the specified distribution, meaning the sample does agree with what the college did report.

Chi-squared test for given probabilities

data: years

X-squared = 3.5846, df = 3, p-value = 0.31We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.31 \ \simeq \ 31 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The sample made do not constitute sufficient evidence to doubt the percentages reported by the college

2nd problem

- 200 rolls of a die result in the following distribution:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 30 | 22 | 31 | 38 | 51 |

Question

Should we conclude that the die is unfair ?

We define the variable years for the sample.

Given the theoretical proportion will be all the same, we do not need to define a vector for the proportions.

Here H0 is that the die is fair.

Chi-squared test for given probabilities

data: counts

X-squared = 15.22, df = 5, p-value = 0.009463We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.001 \ \simeq \ 0.01 \% \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

According to this test we are going to say that the die is unfair.

![]() \(\chi^2\) test for homogeneity

\(\chi^2\) test for homogeneity

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | Qualitative |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitative |

Asumption :

- Each population is at least 10 times as large as its respective sample

- The expected frequency count for each value is at least 5

H0 : Null hypothesis

The distribution of the categorical variable is the same for each subgroup or population

Example :

The author tackle one \(\chi^2\) test for homogeneity using R.

Problem

A random sample of students at two universities resulted in the following distribution of fields of study:

| University | Business | Engineering | Liberal arts | Nursing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 64 | 47 | 145 | 31 |

| B | 41 | 35 | 174 | 52 |

Question

Is it safe to conclude that the populations of students in the two schools have different distributions of fields of study?

We define the vector

students.From

studentswe define the matrixm

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 64 47 145 31

[2,] 41 35 174 52It’s optionnal, but can name the columns and rows.

Business Engineering Liberal arts Nursing

A 64 47 145 31

B 41 35 174 52Now we can perform our \(\chi^2\) test for homogenity.

Here the null hypothesis H0 is that the populations of students in the two schools have the same distribution of fields of study.

We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.002 \ \simeq \ 0.2 \% \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

The populations of students in the two schools have different distributions of fields of study.

![]() \(\chi^2\) test for independence

\(\chi^2\) test for independence

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | Qualitative |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitative |

Asumptions :

- Observations must be independent

- Relatively large sample size

H0 : Null hypothesis

There is no association between the two variables.

Example :

The author tackle a \(\chi^2\) test for independence using R.

The two variables are :

the type of volunteer

the amount of hours spend voluntering

Problem

In a volunteer group, adults 21 and older volunteer from one to nine hours each week to spend time with a disabled senior citizen. The program recruits among :

- community college students,

four-year college students,

and nonstudents.

In the table we have a sample of the adult volunteers and the number of hours they volunteer per week.

| Type of Volunteer | 1-3 Hours | 4-6 Hours | 7-9 Hours | Row Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community College Students | 111 | 96 | 48 | 255 |

| Four-Year College Students | 96 | 133 | 61 | 290 |

| Nonstudents | 91 | 150 | 53 | 294 |

| Column Total | 298 | 379 | 162 | 839 |

Question

Is the number of hours volunteered independent of the type of volunteer?

We define the variable volunteers.

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 111 96 48

[2,] 96 133 61

[3,] 91 150 53We name the columns and the rows.

rownames(volunteers) = c("Community College", "Four Year", "Nonstudent")

colnames(volunteers) = c("1-3 hours", "4-6 hours", "7-9 hours")

volunteers 1-3 hours 4-6 hours 7-9 hours

Community College 111 96 48

Four Year 96 133 61

Nonstudent 91 150 53Now we can perform our \(\chi^2\) indendence test.

Here the null hypothesis is that the two variables are independent.

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: volunteers

X-squared = 12.991, df = 4, p-value = 0.01132We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.01 \ \simeq \ 1 \% \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

It does look like, according to this sample, that the number of hours volunteered is dependent of the type of volunteer.

![]() Binomial test

Binomial test

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | - |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitative (Binary) |

Asumptions :

- Random samples

- Independent observations

- The variable of interest is binary (only two possible outcomes)

- The number of trials is fixed

H0 : Null hypothesis

The population proportion of one outcome equals some claimed value.

Example :

The author tackle a binomial test to see if the proportion of leopards with a solid black coat color equals \(0.35\).

We are going to do it using R.

Problem

According to a genetic model, \(35 \%\) of a certain subspecies of leopards have a solid black coat color.

We believe this rate is lower for leopards living in a wildlife refuge.

So we randomly select 9 unrelated leopards and find that only 1 has a solid black coat.

Question

Is there enough evidence to suggest that the rate is lower than \(35\%\) for leopards living in the refuge.

We define the variables

leopards_sampleleopards_black_coatmodel_proportion

Now we can perform our binomial test

Here the null hypothesis H0 is that the rate is equal to \(45 \%\)

Exact binomial test

data: leopards_black_coat and leopards_sample

number of successes = 1, number of trials = 9, p-value = 0.1747

alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.35

95 percent confidence interval:

0.002809137 0.482496515

sample estimates:

probability of success

0.1111111 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.17 \ \simeq \ 17 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The rate of \(35 \%\) given by the genetic model seems to be correct

![]() Tests for normality

Tests for normality

To check for normality, :

- Graphical methods

- Histogram

- Boxplot

- Density plot

- QQ plot

- Statistical tests

- Shapiro-Wilk test

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

![]() Graphical method

Graphical method

First we load the required packages

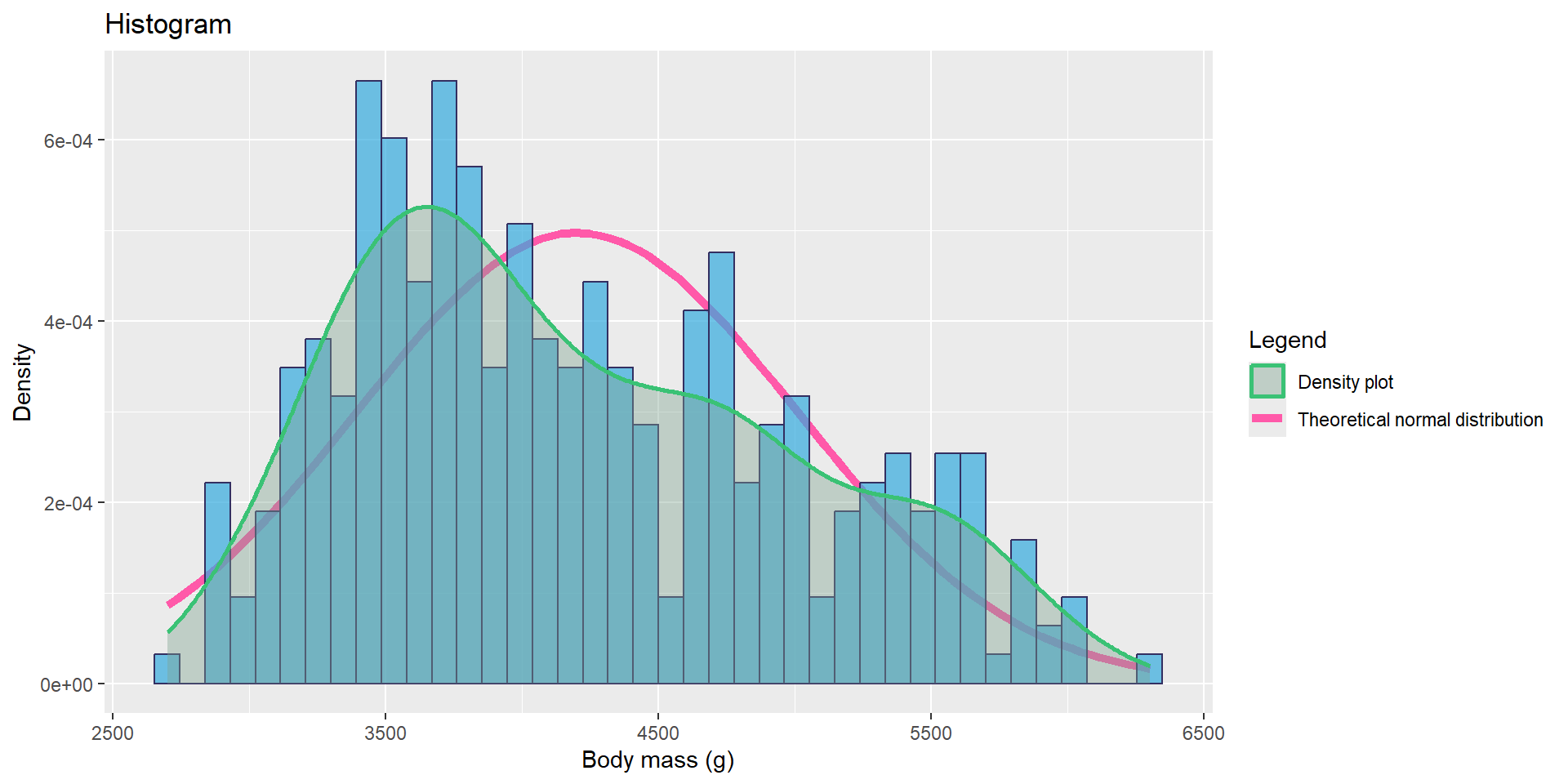

Histogram, density plot

It gives an idea on the chance for the variable to be normal.

We can plot at the same time :

- the histogram

- the density plot

- the theoretical normal distribution density

penguins.mean = mean(penguins$body_mass_g, na.rm = TRUE)

penguins.sd = sd(penguins$body_mass_g, na.rm = TRUE)

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = body_mass_g)) +

# Colors for the two curves

scale_color_manual(name = "Legend",

values = c("Density plot" = "#3AC275",

"Theoretical normal distribution" = "#FF59A9")) +

# Theretical curve

geom_line(stat = "function",

fun = dnorm, #normal distribution density function

args = list(mean = penguins.mean, sd = penguins.sd),

aes(color = "Theoretical normal distribution"),

linewidth = 1.8) +

# Histogram

geom_histogram(aes(y = after_stat(density)), #plot histogram using density, not counts

na.rm = TRUE,

bins = 40,

alpha=0.7,

fill="#33AADE",

color="#332F61") +

# Density plot

geom_density(na.rm = TRUE,

alpha=0.4,

aes(color = "Density plot"),

linewidth = 1,

fill="#7EA38F") +

# Title-s

labs(title = "Histogram", x = "Body mass (g)", y = "Density") +

# Side legend

theme(legend.position = "right")

The variable body_mass_g does not look like it follows a normal distribution.

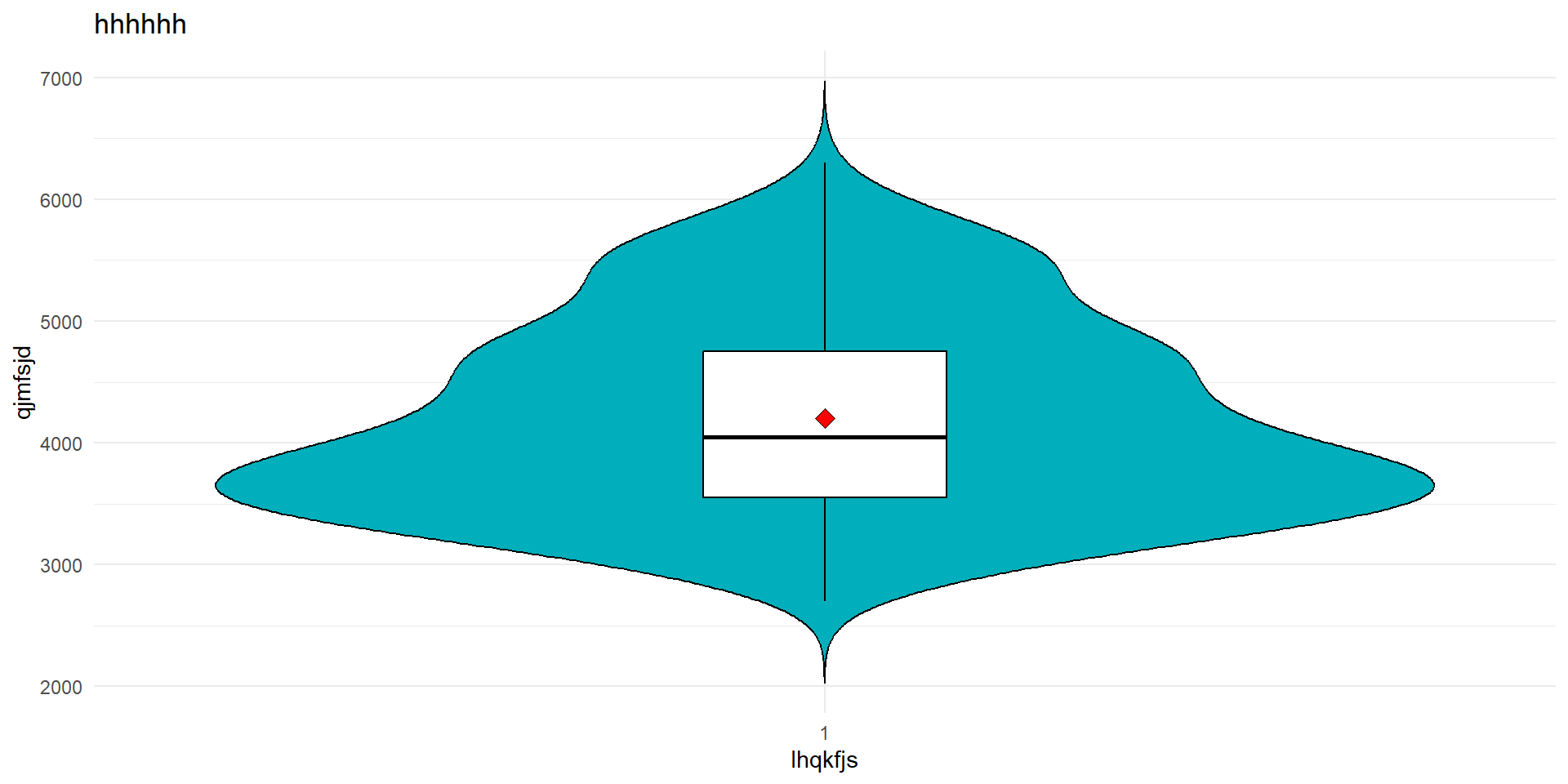

Boxplot (and violin plot)

- Boxplot : A normal distribution is symmetric, thus if :

- the median line inside the box is roughly in the center of the box,

- and the length of the whiskers are roughly equal on both sides, then we might have a normal distribution

- Violin plot :

- The width at a given value represents the density (how many points are near that value).

- Wide sections \(\to\) many observations.

- Narrow sections \(\to\) few observations

library(ggpubr)

library(dplyr)

library(palmerpenguins)

# Remove rows with NA in body_mass_g

penguins_clean <- penguins %>%

filter(!is.na(body_mass_g))

# Create the plot

ggviolin(penguins_clean,

y = "body_mass_g",

fill = "#00AFBB",

add = "boxplot",

add.params = list(fill = "white")) +

labs(title = "hhhhhh",

y = "qjmfsjd",

x = "lhqkfjs") +

theme_minimal() +

stat_summary(fun = mean, geom = "point", shape = 23, size = 3, fill = "red")

Same conclusion the variable body_mass_g does not look like it follows a normal distribution.

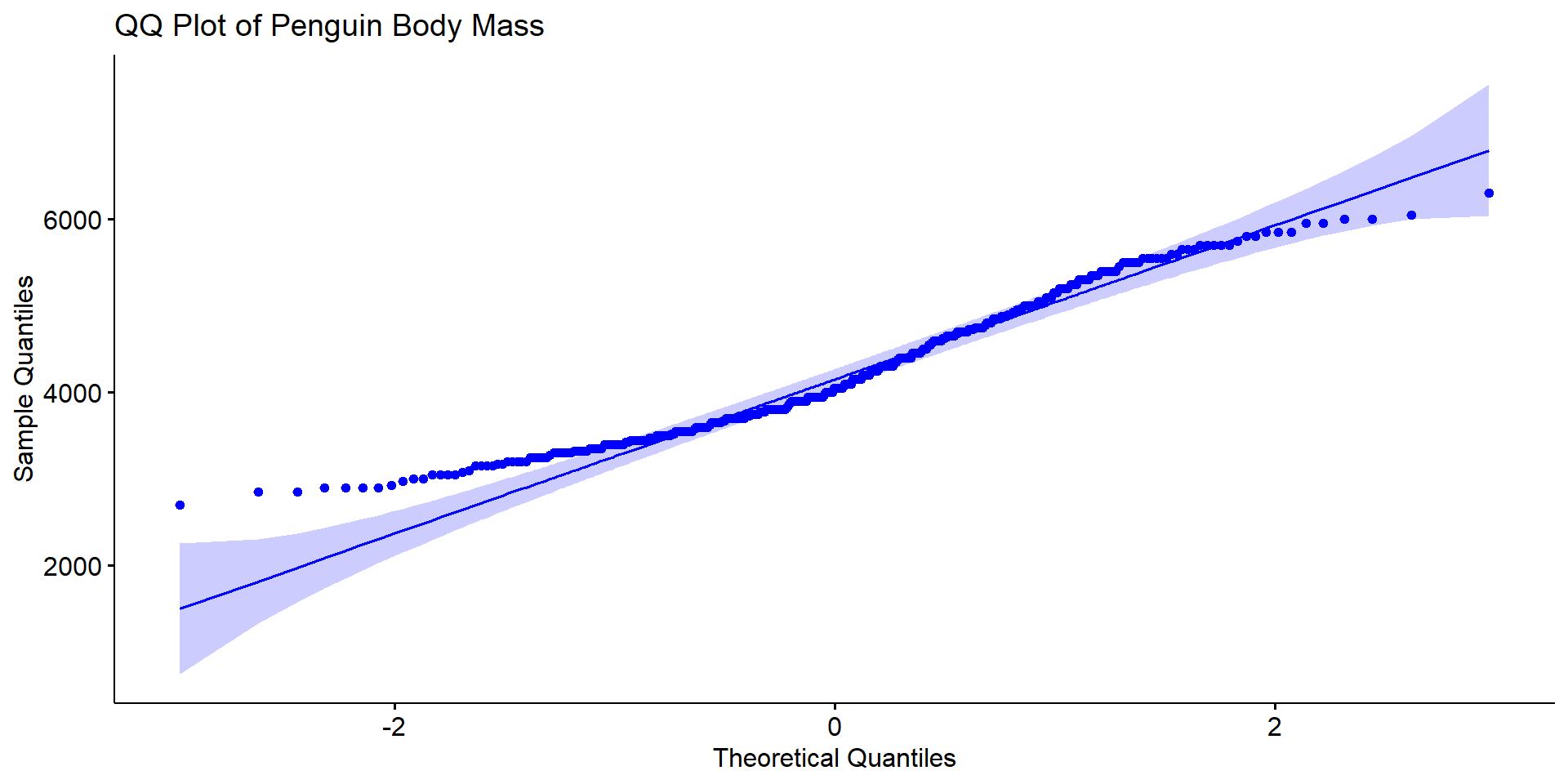

QQ plot

- A Q–Q plot compares the quantiles of your data to the quantiles of a theoretical normal distribution.

- If the data are normally distributed, the points should fall roughly on a straight diagonal line.

# Remove NA values from body_mass_g

body_mass <- na.omit(penguins$body_mass_g)

# Create a QQ plot

ggqqplot(body_mass,

title = "QQ Plot of Penguin Body Mass",

xlab = "Theoretical Quantiles",

ylab = "Sample Quantiles",

color = "blue",

shape = 19)

Again the ame conclusion, the variable body_mass_g does not look like it follows a normal distribution.

![]() Shapiro-Wilk Test

Shapiro-Wilk Test

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | / |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Quantitative |

Asumption :

- The sample size is small to moderate (e.g. less than 2000 observations).

H0 : Null hypothesis

The sample comes from a normal distribution.

Example :

The author tackle Shapiro-Wilk Nnormality test using R.

The data will be created directly in R using the comand

set.seed.

Question

Are the two variables normally distributed ?

We apply a shapiro test for the two variables.

We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.55 \ \simeq \ 55 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The sample X1 does look like it is normally distributed

We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 7.5 \ 10^{-5} \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

The sample X2 does NOT look like it is normally distributed

![]() Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | / |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Quantitative |

Asumption :

- /

H0 : Null hypothesis

The sample comes from a normal distribution.

Example :

We create a variable Y :

We are going to use the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for an normal distribution.

It is written like this :

ks.test(Y, "pnorm", mean = mean(Y), sd = sd(Y))

Asymptotic one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

data: Y

D = 0.23999, p-value = 0.6122

alternative hypothesis: two-sidedWe get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.61 \ \simeq \ 61 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The sample Y does look like it is normally distributed

![]() Tests for homogeneity of variances

Tests for homogeneity of variances

There are two main tests.

![]() Levene test

Levene test

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | Quantitative |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitative |

Asumption :

- Independent observations

H0 : Null hypothesis

The variance among groups is equal.

Example :

We import the dataset titanic.csv

we load the required packages

Question

In the dataset titanic, do the two groups deadand alive have the same variance ?

we perform our levene test

Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

Df F value Pr(>F)

group 1 5.1144 0.02407 *

631

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.024 \ \simeq \ 2.4 \% \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

The two groups do not have the same variance.

![]() Bartlett test

Bartlett test

Non-parametric test

| Dependent variable | Quantitative |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitative |

Asumption :

- It does not assume equal sample sizes across groups

H0 : Null hypothesis

The variance among groups is equal.

Example :

We use the same dataset titanic, but this time we change variable.

Question

In the dataset titanic, do the two groups femaleand male have the same variance ?

Bartlett test of homogeneity of variances

data: age by sex

Bartlett's K-squared = 0.049888, df = 1, p-value = 0.8233We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.82 \ \simeq \ 8.2 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The two groups have the same variance.

![]() T-tests

T-tests

There are different T-tests.

![]() T-test for one sample

T-test for one sample

Parametric test

| Dependent variable | Quantitative (continuous) |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | - |

Asumptions :

Normality : dependent variables should be normally distributed within each group

Homogenity of variance

H0 : Null hypothesis

The sample mean is equal to the given reference value

Example :

We collect a sample of 10 birth weight of sheep.

There are not outliers.

The null hypothesis H0 is : \(\mu = 3.5\), and we chose \(\alpha = 5 \%\).

One Sample t-test

data: weight

t = -3.6122, df = 9, p-value = 0.00564

alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 3.5

95 percent confidence interval:

1.955063 3.144937

sample estimates:

mean of x

2.55 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.006 \ \simeq \ 0.6 \% \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0. The mean of the dataset if not equal to \(3.5\).

We can ask ourselves if the mean of the dataset is less or greater than \(3.5\).

The null hypothesis is just a bit different :

H0 : \(\mu < 3.5\)

One Sample t-test

data: weight

t = -3.6122, df = 9, p-value = 0.9972

alternative hypothesis: true mean is greater than 3.5

95 percent confidence interval:

2.067899 Inf

sample estimates:

mean of x

2.55 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.997 \ \simeq \ 99.7 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accep H0. The mean of the dataset if less than \(3.5\).

![]() Independent t-test

Independent t-test

Parametric test

| Dependent variable | Quantitative (continuous) |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitatite (2 groups) |

Asumptions :

Normality : dependent variables should be normally distributed within each group

\(\to\) if not met : Mann-Whitney testHomogenity of variance

Does not assume equal sample sizes or equal variances between groups

Assumes independent observations drawn from normally-distributed populations

Robust against violations of normality when sample size is large

H0 : Null hypothesis

The groups have equal means.

Example :

We load the dataset bocks from the library GLMsData

we perform our t-test

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: Number by Shape

t = 7.4956, df = 77.669, p-value = 9.056e-11

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group Cube and group Cylinder is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

1.96814 3.39186

sample estimates:

mean in group Cube mean in group Cylinder

8.16 5.48 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 9.05 \ 10^{-11} \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

The two groups do NOT have the same mean.

![]() Paired t-test

Paired t-test

Parametric test

| Dependent variable | Quantitative (continuous) |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Time point 1 or 2 /condition |

Asumptions :

- Normality : dependent variables should be normally distributed within each group

\(\to\) if not met : Wilcoxon test

H0 : Null hypothesis

The groups have equal means.

Example :

# Weight of the mice before treatment

before <-c(200.1, 190.9, 192.7, 213, 241.4, 196.9, 172.2, 185.5, 205.2, 193.7)

# Weight of the mice after treatment

after <-c(392.9, 393.2, 345.1, 393, 434, 427.9, 422, 383.9, 392.3, 352.2)

# Create a data frame

my_data <- data.frame(

group = rep(c("before", "after"), each = 10),

weight = c(before, after)

)

my_data group weight

1 before 200.1

2 before 190.9

3 before 192.7

4 before 213.0

5 before 241.4

6 before 196.9

7 before 172.2

8 before 185.5

9 before 205.2

10 before 193.7

11 after 392.9

12 after 393.2

13 after 345.1

14 after 393.0

15 after 434.0

16 after 427.9

17 after 422.0

18 after 383.9

19 after 392.3

20 after 352.2we perfrom our paired t-test

Paired t-test

data: before and after

t = -20.883, df = 9, p-value = 6.2e-09

alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-215.5581 -173.4219

sample estimates:

mean difference

-194.49 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 6.2 \ 10^{-9} \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

The two groups do NOT have the same mean.

![]() Mann-Whitney test

Mann-Whitney test

Non-parametric equivalent to the independent t-test

| Dependent variable | Ordinal/ Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitative |

Asumption :

- independent samples

There are two types Mann-Whitney tests. If the distribution of scores for both groups have the same shape, the medians can be compared. If not, use the default test which compares the mean ranks

H0 : Null hypothesis

The median of the two groups are the same (if the distribution for both groups have the same shape), otherwise the mean ranks are the same.

Example :

movieRating = read.csv(file = "data_raw/95_Data_File.csv", header = TRUE, sep = ",")

head(movieRating) Male Female

1 6.35 5.90

2 6.54 6.28

3 6.11 5.76

4 6.97 6.66

5 6.78 6.71

6 5.83 5.58

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: movieRating$Male and movieRating$Female

W = 255.5, p-value = 0.1368

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.1368 \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The two groups do have the same median.

![]() Wilcoxon test

Wilcoxon test

Non-parametric equivalent to the paired t-test

| Dependent variable | Ordinal/ Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Time/ Condition |

Asumption : /

H0 : Null hypothesis

The is no median difference between the paired observations.

Example :

Clone August November

1 Primo 12.6 12.7

2 Raspalje 9.5 10.5

3 Hazendans 16.5 15.3

4 Hoogvorst 13.6 15.6

5 Fritzi Pauley 13.3 11.1

6 Balsam Spire 8.1 11.2

Wilcoxon signed rank exact test

data: aluLevels$August and aluLevels$November

V = 16, p-value = 0.03979

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.039 \ = \ 0.39 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

The two groups do NOT have the same median.

![]() ANOVA

ANOVA

ANalysis Of VAriance

![]() One-way ANOVA

One-way ANOVA

Parametric test

| Dependent variable | Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitatives (3+ groups) |

Asumptions :

- Residuals should be normally distributed

\(\to\) if not met : Kruskall-Wallis test

- Homogeneity of variance

H0 : Null hypothesis

The population means are all equal in the groups.

Example :

We load the required packages and the dataset chickwts

weight feed

1 179 horsebean

2 160 horsebean

3 136 horsebean

4 227 horsebean

5 217 horsebean

6 168 horsebeanQuestion

Does the feed being used help explain the weights of chicken ?

We first look for homogeneity of variance.

Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

Df F value Pr(>F)

group 5 0.7493 0.5896

65 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.59 \ = \ 59 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The groups do have the same variance

We need to check if the residuals are normally distributed

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: model.ANOVA.OneWay$residuals

W = 0.98616, p-value = 0.6272We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.63 \ = \ 63 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The residuals are normally distributed

Now we can analyse the ANOVA result :

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

chickwts$feed 5 231129 46226 15.37 5.94e-10 ***

Residuals 65 195556 3009

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 5.94 . 10^{-10} \ < \alpha\)

Therefore we can reject H0.

The mean are not the same all the groups.

The feed being used help explain the weights of chicken, but we cannot say how.

![]() Two-way ANOVA

Two-way ANOVA

Parametric test

| Dependent variable | Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independent variables | 2 qualitative (2+ levels within each) |

Asumptions :

Residuals should be normally distributed

Homogeneity of variance

H0 : Null hypothesis

The means (by one factor) of the groups being compared are the same

The means (by the other factor) of the groups being compared are the same

There is no interaction between the two factors

The two-way ANOVA : extension of the one-way ANOVA that examines the influence of two different categorical independent variables on one continuous dependent variable.

The two-way ANOVA not only aims at assessing the main effect of each independent variable but also if there is any interaction between them.

Example :

len supp dose

1 4.2 VC 0.5

2 11.5 VC 0.5

3 7.3 VC 0.5

4 5.8 VC 0.5

5 6.4 VC 0.5

6 10.0 VC 0.5We first look for homogeneity of variance.

Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

Df F value Pr(>F)

group 5 1.7086 0.1484

54 We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.15 \ = \ 15 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

We have the homogeneity of variance.

We need to check if the residuals are normally distributed

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: model.ANOVA.TwoWay$residuals

W = 0.98499, p-value = 0.6694We get a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.67 \ = \ 67 \% \ > \alpha\)

Therefore we can accept H0.

The residuals are normally distributed

Now we can analyse the Two-way ANOVA result :

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

supp 1 205.4 205.4 15.572 0.000231 ***

factor(dose) 2 2426.4 1213.2 92.000 < 2e-16 ***

supp:factor(dose) 2 108.3 54.2 4.107 0.021860 *

Residuals 54 712.1 13.2

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1- We get the a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.000231 \ < \alpha\)

- Therefore we can reject the first part of the null hypothesis, which is : \(\to\) The means (by the factor

supp) of the groups are NOT the same

- Therefore we can reject the first part of the null hypothesis, which is : \(\to\) The means (by the factor

- We get the a p-value \(\simeq \ 2 10^{-16} \ < \alpha\)

- Therefore we can reject the second part of the null hypothesis, which is : \(\to\) The means (by the factor

factor(dose)) of the groups are NOT the same

- Therefore we can reject the second part of the null hypothesis, which is : \(\to\) The means (by the factor

- We get the a p-value \(\simeq \ 0.022 \ < \alpha\)

- Therefore we can reject the third part of the null hypothesis, which is : \(\to\) There IS an interaction between the two factors

![]() Post hoc tests

Post hoc tests

In order to find out exactly which groups are different from each other, we must conduct a post hoc test.

The Tukey test : compare all groups to each other

The Dunnett test : compare with a reference group.

![]() The Tukey test

The Tukey test

Often follows a one-way ANOVA

| Dependent variable | Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitatives (3+ groups) |

Asumptions :

the observations are independent,

normality of distribution,

homogeneity of variance.

H0 : Null hypothesis

The means of the tested groups are equal

Example 1 :

Diet Weight.Week.1 Weight.Week.8 Weight.Loss

1 1 59 55 4

2 1 61 55 6

3 1 65 64 1

4 1 65 62 3

5 1 66 63 3

6 1 67 65 2Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

Df F value Pr(>F)

group 2 2.8097 0.06657 .

75

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1therefore we have homogeneity of variance

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: anova.tukey$residuals

W = 0.98329, p-value = 0.3995therefore we have normality

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

factor(Diet) 2 69.4 34.7 6.551 0.00239 **

Residuals 75 397.3 5.3

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1therefore the means bewtween the groups are not the same

Tukey multiple comparisons of means

95% family-wise confidence level

Fit: aov(formula = Weight.Loss ~ factor(Diet), data = dietData)

$`factor(Diet)`

diff lwr upr p adj

2-1 0.3796296 -1.1643251 1.923584 0.8270005

3-1 2.1574074 0.6134526 3.701362 0.0036876

3-2 1.7777778 0.2799216 3.275634 0.0159151only the comparison between groups 3 and 1 do have a p-value that indicate they might have different means

Example 2 :

We create our dataset

# response variable

size <- c(25,22,28,24,26,24,22,21,23,25,26,30,25,24,21,27,28,23,25,24,20,22,24,23,22,24,20,19,21,22)

# predictor variable

location <- as.factor(c(rep("ForestA",10), rep("ForestB",10), rep("ForestC",10)))

# dataframe

my.dataframe <- data.frame(size,location)

head(my.dataframe) size location

1 25 ForestA

2 22 ForestA

3 28 ForestA

4 24 ForestA

5 26 ForestA

6 24 ForestAwe check the homegeniety of variance

Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

Df F value Pr(>F)

group 2 0.4919 0.6168

27 according to the p-value we have the homogeneity of variance

we check for the normality

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: size[1 - 10]

W = 0.97115, p-value = 0.5913

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: size[11 - 20]

W = 0.97115, p-value = 0.5913

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: size[21 - 30]

W = 0.97115, p-value = 0.5913according to the p-values we have the normality

we perform our one-way ANOVA

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

location 2 66.47 33.23 7.11 0.00331 **

Residuals 27 126.20 4.67

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1according to the p-value the means of the groups are not equal

we then perfrom our Tukey test

Tukey multiple comparisons of means

95% family-wise confidence level

Fit: aov(formula = size ~ location, data = my.dataframe)

$location

diff lwr upr p adj

ForestB-ForestA 1.3 -1.097245 3.69724537 0.3835917

ForestC-ForestA -2.3 -4.697245 0.09724537 0.0619108

ForestC-ForestB -3.6 -5.997245 -1.20275463 0.0025530The output displays the results of all pairwise comparisons among the tested groups.

The p-value for the comparison Forest B with Forest A is bigger than \(\alpha\).

- Therefore their means are equal

The p-value for the other comparisons are smaller than \(\alpha\).

- Therefore their means are NOT equal

![]() The Dunnett test

The Dunnett test

Often follows a one-way ANOVA

| Dependent variable | Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitatives (3+ groups) |

Asumptions :

- Groups being compared must be independent

H0 : Null hypothesis

The means of the control group and any other groups are the equal

Example :

We go back with our example from the tukey test.

We chose the forest A has a reference.

Dunnett's test for comparing several treatments with a control :

95% family-wise confidence level

$ForestA

diff lwr.ci upr.ci pval

ForestB-ForestA 1.3 -0.9562769 3.5562769 0.3160

ForestC-ForestA -2.3 -4.5562769 -0.0437231 0.0453 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1- The p-value for the comparison Forest B with Forest A is bigger than \(\alpha\).

- Therefore their means are equal

- The p-value for the comparison Forest C with Forest A is smaller than \(\alpha\).

- Therefore their means are NOT equal

![]() Kruskal-Wallis test

Kruskal-Wallis test

Non parametric equivalent to the one-way ANOVA

| Dependent variable | Ordinal / Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Qualitatives (3+ groups) |

Asumptions :

the observations are independent

similar sample size

H0 : Null hypothesis

The mean ranks of the groups are the same.

Example :

Type.A Type.B Type.C Type.D Type.E Type.F

1 10 11 0 3 3 11

2 7 17 1 5 5 9

3 20 21 7 12 3 15

4 14 11 2 6 5 22

5 14 16 3 4 3 15

6 12 14 1 3 6 16we perform our Kruskal-Wallis test

Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test

data: sprayData

Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 54.691, df = 5, p-value = 1.511e-10we get a very small p-value, therefore we can reject H0

![]() Correlation-s tests

Correlation-s tests

Non parametric equivalent to the one-way ANOVA

| Dependent variable | Continuous |

|---|---|

| Independant variable | Continuous |

Asumptions :

H0 : Null hypothesis

There is no linear relationship

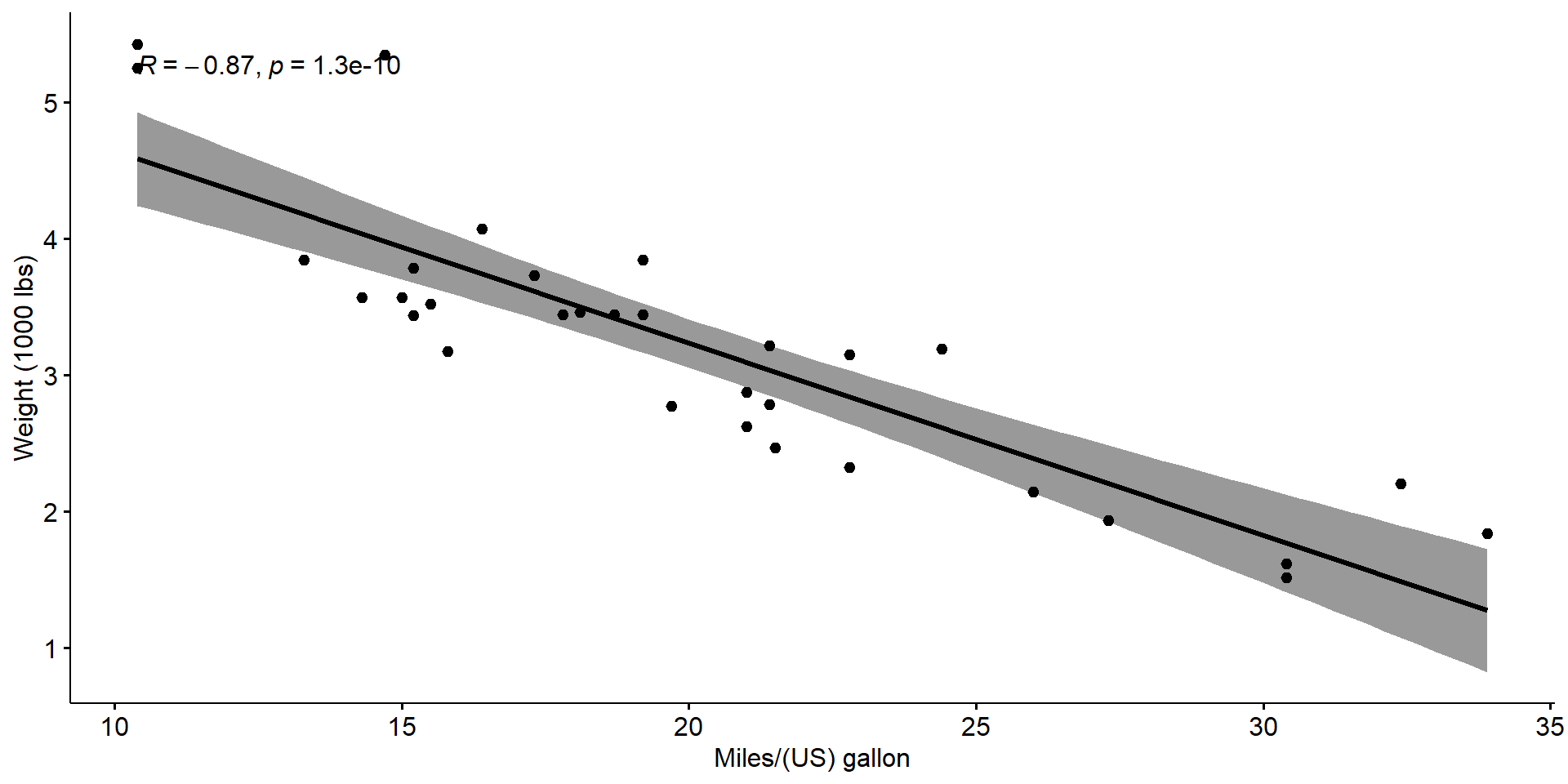

Example :

We load the required packages

Correlation coefficient can be computed using the functions cor or cor.test

we can choose between 3 methods :

pearsonkendallspearman

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 0 1 4 4

Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

Datsun 710 22.8 4 108 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 1 1 4 1

Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258 110 3.08 3.215 19.44 1 0 3 1

Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360 175 3.15 3.440 17.02 0 0 3 2

Valiant 18.1 6 225 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 1 0 3 1we plot our data

ggscatter(my_data, x = "mpg", y = "wt",

add = "reg.line", conf.int = TRUE,

cor.coef = TRUE, cor.method = "pearson",

xlab = "Miles/(US) gallon", ylab = "Weight (1000 lbs)")

The Pearson correlation test

Pearson's product-moment correlation

data: my_data$wt and my_data$mpg

t = -9.559, df = 30, p-value = 1.294e-10

alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.9338264 -0.7440872

sample estimates:

cor

-0.8676594 - The p-value is less than \(\alpha\)

- We can conclude that

wtandmpgare significantly correlated with a correlation coefficient of \(-0.87\)

Kendall rank correlation test

Kendall's rank correlation tau

data: my_data$wt and my_data$mpg

z = -5.7981, p-value = 6.706e-09

alternative hypothesis: true tau is not equal to 0

sample estimates:

tau

-0.7278321 same conclusion as the Pearson correlation test

Spearman rank correlation coefficient

Spearman's rank correlation rho

data: my_data$wt and my_data$mpg

S = 10292, p-value = 1.488e-11

alternative hypothesis: true rho is not equal to 0

sample estimates:

rho

-0.886422 same conclusion as the previous correlation tests

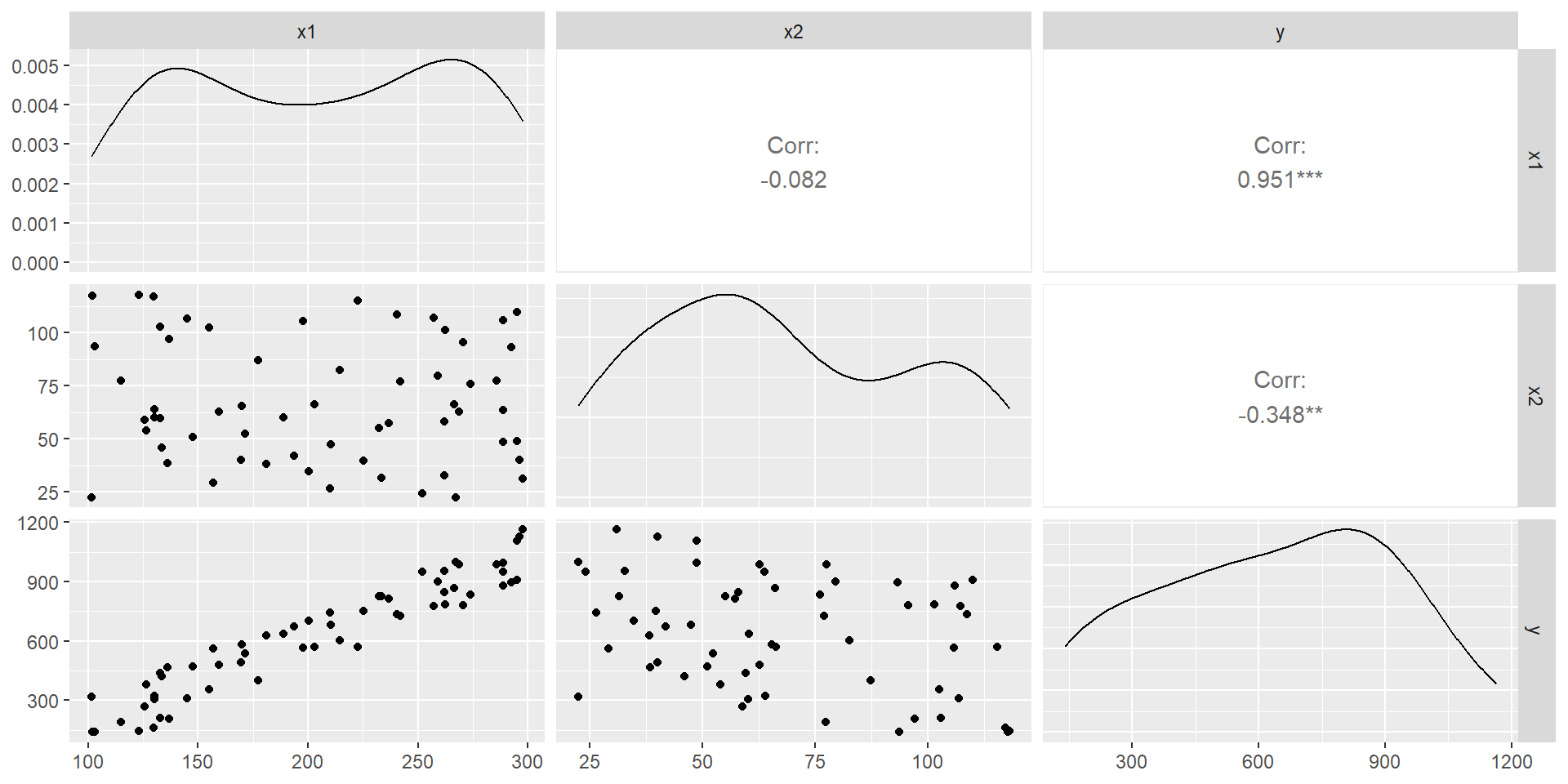

![]() Multiple Linear regression

Multiple Linear regression

Few packages that are very useful to perform multiple linear regression

We “produce” data (FYI)

our dataset is

# A tibble: 6 × 3

x1 x2 y

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 137. 97.0 205.

2 240. 109. 737.

3 215. 82.5 603.

4 134. 46.0 423.

5 289. 106. 878.

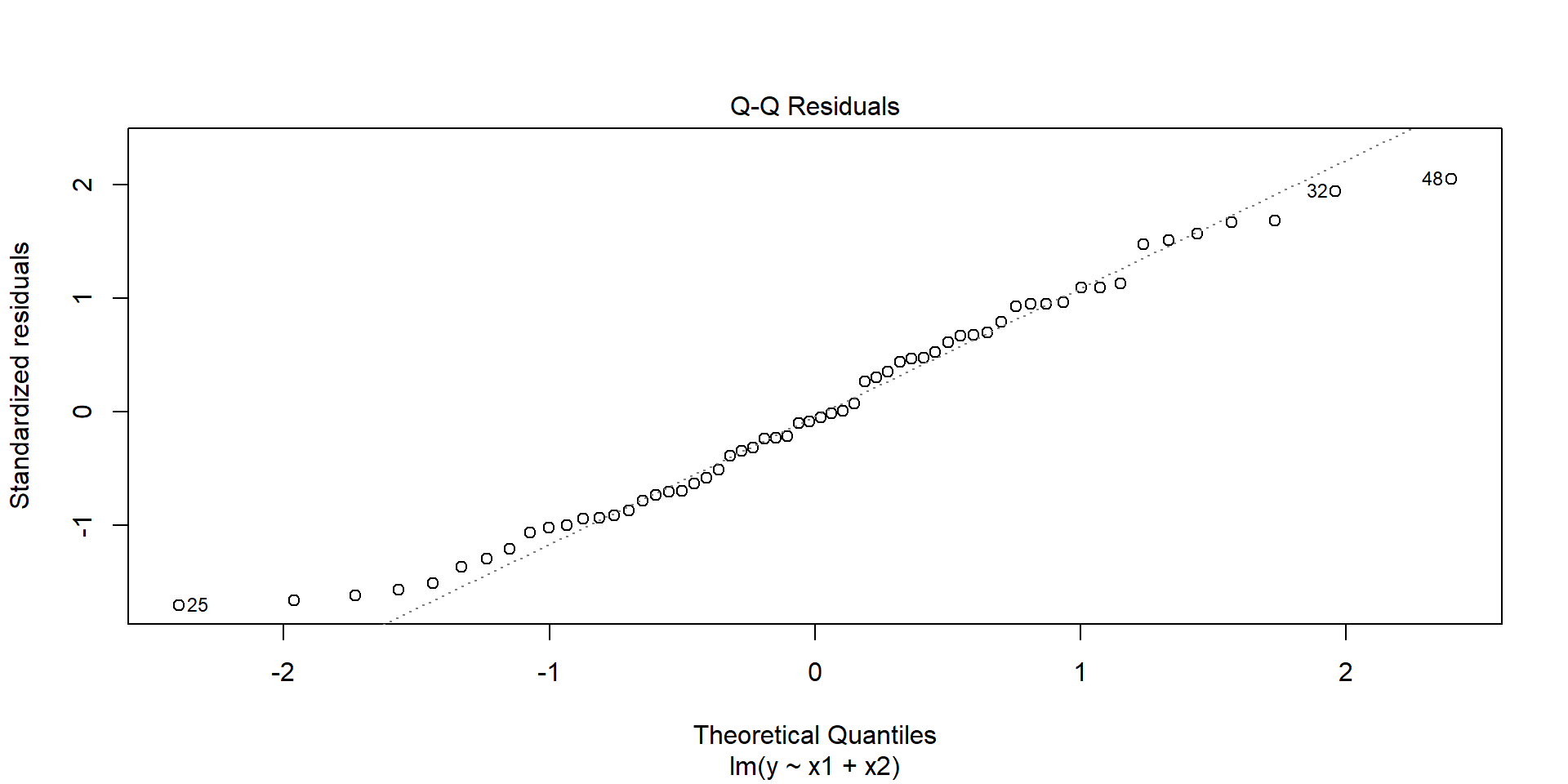

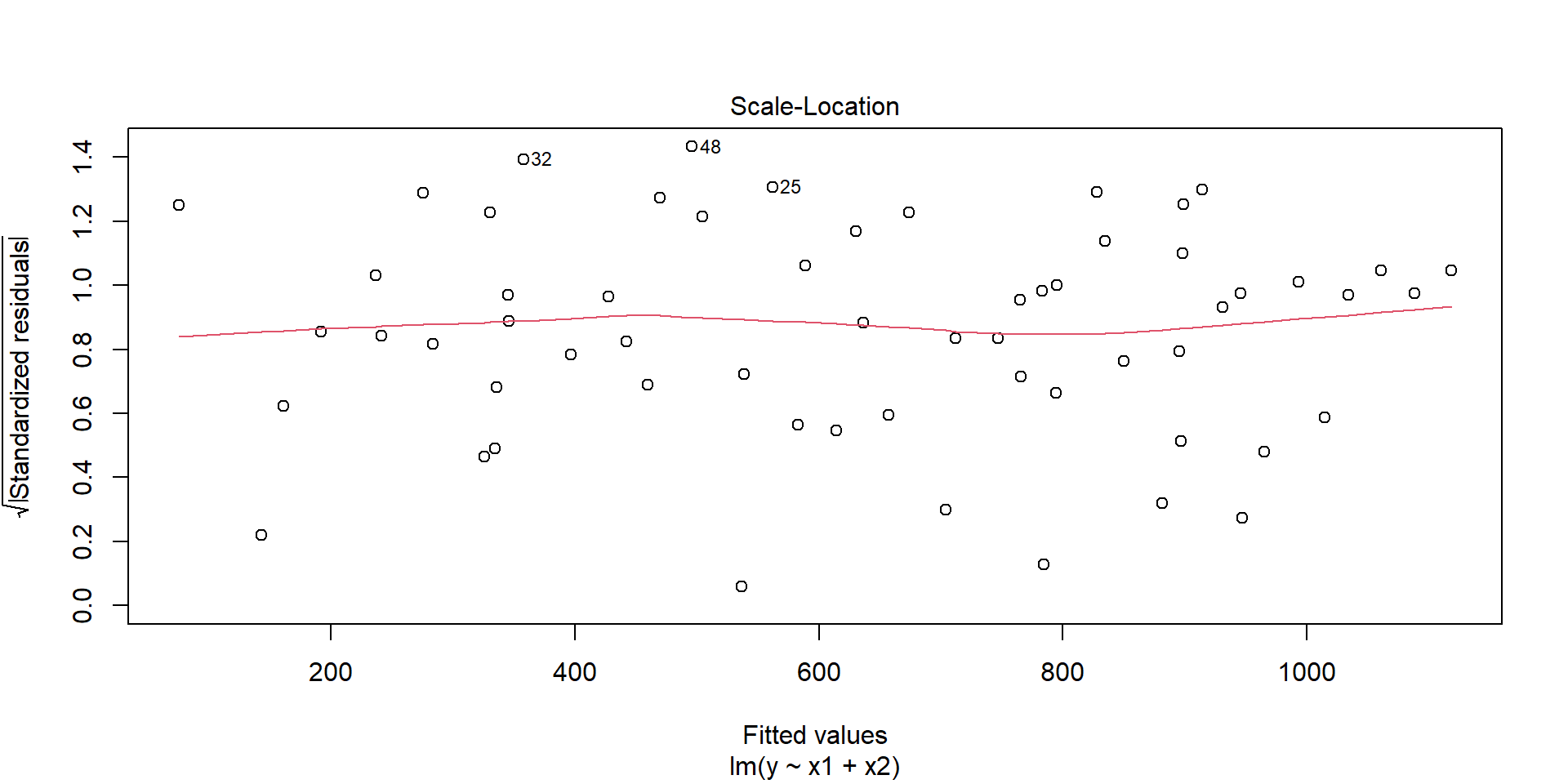

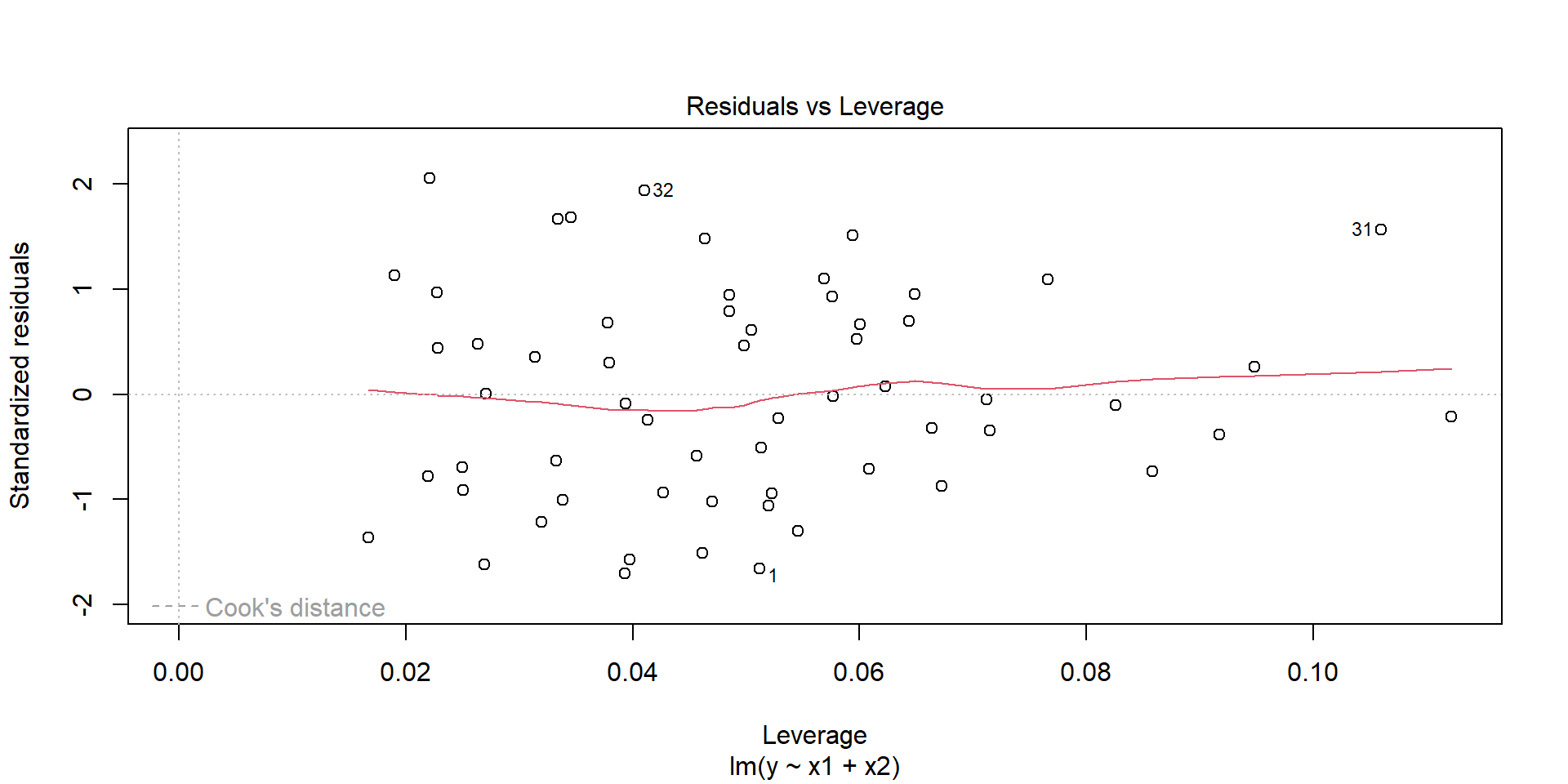

6 289. 63.7 951.Assumptions

Model of the form

\[y \sim \beta_0+\displaystyle\sum_{k=1}^p \beta_k x_k+\epsilon_i\]

- Assumes Linear relationship between \(y\) and \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_p\)

- Assumes the irreducible error (\(\epsilon_i\)) is normally distributed

- Assumes homoscedacisity, that is \(\epsilon_i\) does not depend on \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_p\)

- In this model, the variables \(x_i\) do not interact

- Always watch out for outliers !

A first look at the data

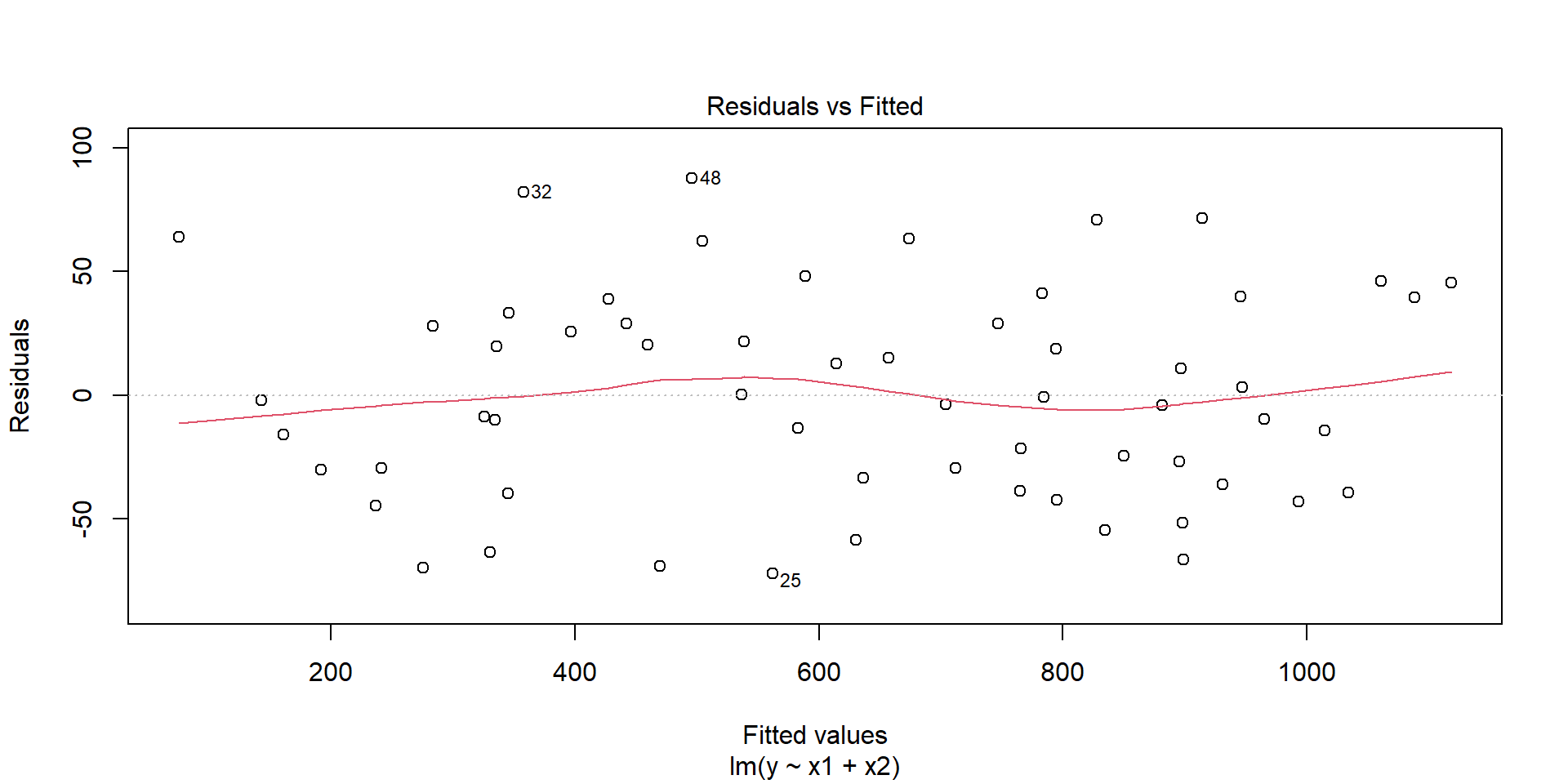

The model

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x1 + x2, data = df)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-72.286 -34.102 -2.892 30.163 87.738

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -35.39079 24.19773 -1.463 0.149

x1 4.15232 0.08981 46.235 <2e-16 ***

x2 -2.66124 0.19657 -13.539 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 43.2 on 57 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9772, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9764

F-statistic: 1220 on 2 and 57 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Few graphs to undersand the model

Predictions

# A tibble: 20 × 2

x1 x2

<dbl> <dbl>

1 120 101.

2 129. 54.1

3 139. 74.4

4 148. 90.4

5 158. 107.

6 167. 106.

7 177. 56.7

8 186. 71.3

9 196. 41.9

10 205. 58.5

11 215. 86.4

12 224. 36.4

13 234. 50.1

14 243. 34.1

15 253. 89.1

16 262. 31.1

17 272. 33.4

18 281. 52.5

19 291. 33.3

20 300 80.6\(\to\) We want to “predict” the y according to these x1 and x2

# A tibble: 20 × 3

x1 x2 predict

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 120 101. 193.

2 129. 54.1 358.

3 139. 74.4 344.

4 148. 90.4 340.

5 158. 107. 337.

6 167. 106. 377.

7 177. 56.7 548.

8 186. 71.3 548.

9 196. 41.9 666.

10 205. 58.5 661.

11 215. 86.4 626.

12 224. 36.4 799.

13 234. 50.1 802.

14 243. 34.1 883.

15 253. 89.1 777.

16 262. 31.1 970.

17 272. 33.4 1003.

18 281. 52.5 992.

19 291. 33.3 1082.

20 300 80.6 996.Factor analysis

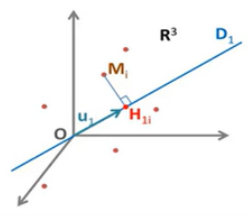

![]() Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis

Problem

We are working with a problem with way too many dimensions

Goals

Dimension reduction to a few dimensions while explaining most of the variance

Find one-dimensional index that separates objects best

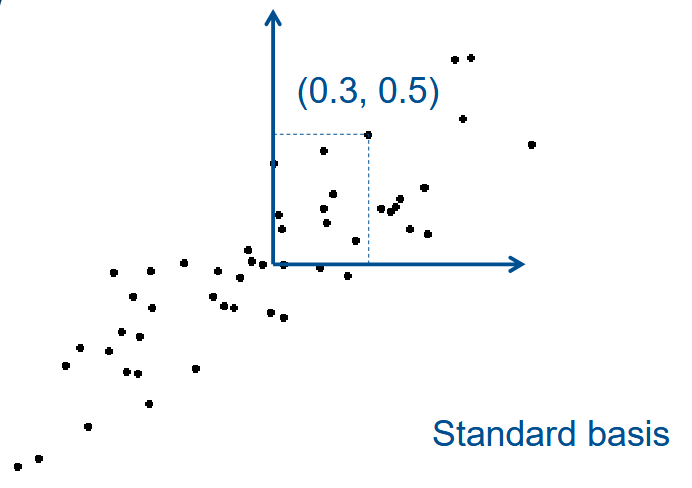

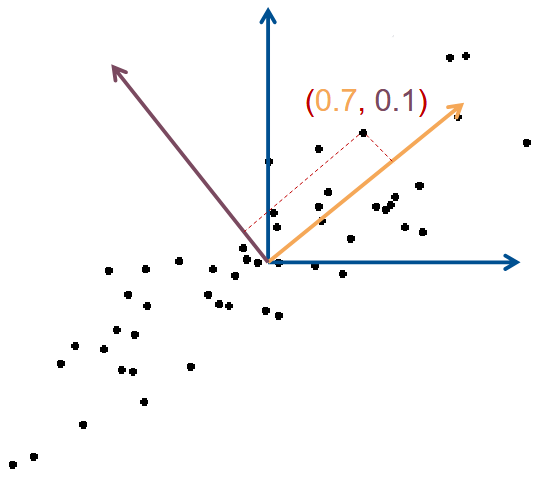

Intuition

Note

Find low-dimensional projection with largest spread

Dimension reduction : Only keep coordinate of first (few) Principal Component (PC)

Rotated basis :

- Vector 1 : Largest variance (1st PC)

- Vector 2 : Perpendicular (2nd PC)

| x1 | x2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Std. Basis | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| PC Basis | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| After Dim. Reduc. | 0.7 | - |

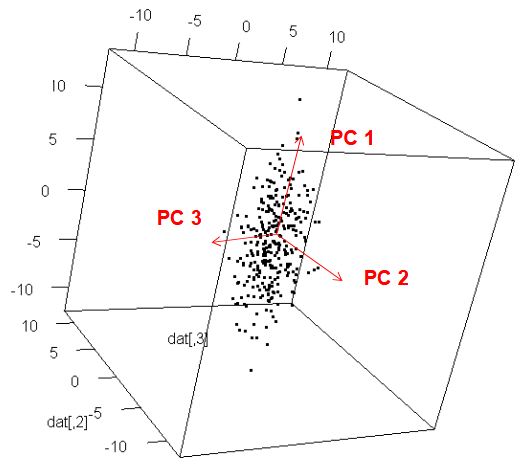

Orthogonal directions

PC 1 is the direction with largest variance

PC 2 is :

- perpendicular to PC 1

- again largest variance

PC 3 is :

- perpendicular to PC 1, PC 2

- again largest variance

…

Which kinds of data ?

PCA applies to data tables where : - rows are considered as individuals - and columns as quantitative variables

Example :

The data :

| \(P\) \(\left(\text{cm}\right)\) | \(T_{\text{max}}\) \(\left(^\circ C\right)\) | \(T_{\text{min}}\) \(\left(^\circ C\right)\) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ajaccio | 12,04 | 23,7 | 5,9 |

| Brest | 17,18 | 15,5 | -1,8 |

| Dunkerque | 11,83 | 13,1 | 2,8 |

| Nancy | 6,23 | 13,5 | -2,4 |

| Nice | 16,99 | 21,1 | 7,2 |

| Toulouse | 3,87 | 20,3 | -0,9 |

| \(\mu\) | 11,36 | 17,87 | 1,8 |

| \(\sigma\) | 4,98 | 4,04 | 3,76 |

We can center and reduce this dataset using the relation

\[x_{i k}=\frac{x_{i k}-\overline{X_k}}{\sigma_k}\] we get

| \(P\) \(\left(\text{cm}\right)\) | \(T_{\text{max}}\) \(\left(^\circ C\right)\) | \(T_{\text{min}}\) \(\left(^\circ C\right)\) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ajaccio | 0,14 | 1,44 | 1,09 |

| Brest | 1,17 | -0,59 | -0,96 |

| Dunkerque | 0,10 | -1,18 | 0,27 |

| Nancy | -1,03 | -1,08 | -1,12 |

| Nice | 1,13 | 0,80 | 1,44 |

| Toulouse | -1,50 | 0,60 | -0,72 |

We call it \(X_{cr}\)

\[X_{cr} =\left[\begin{array}{rrr}0,14 & 1,44 & 1,09 \\ 1,17 & -0,59 & -0,96 \\ 0,10 & -1,18 & 0,27 \\ -1,03 & -1,08 & -1,12 \\ 1,13 & 0,80 & 1,44 \\ -1,50 & 0,60 & -0,72\end{array}\right]\]

we can define the correlation Matrix

| \(P\) | \(T_{\text{max}}\) | \(T_{\text{min}}\) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(P\) | 1 | \(r\left(P, T_{\text{max} }\right)\) | \(r\left(P, T_{\text{min} }\right)\) |

| \(T_{\text{max} }\) | \(r\left(T_{\text{max} }, P\right)\) | 1 | \(r\left(T_{\text{max} }, T_{\text{min} }\right)\) |

| \(T_{\text{min} }\) | \(r\left(T_{\text{min} }, P\right)\) | \(r\left(T_{\text{min} }, T_{\text{max} }\right)\) | 1 |

where \(r\) are the correlations between 2 variables

\[r\left(P, T_{\text{max} }\right) = r\left(T_{\text{max} }, P\right)\]

\[C = \frac{1}{N} \ X_{cr}^T \ X_{cr}\] where here \(N=6\).

| \(P\) | \(T_{\text{max} }\) | \(T_{\text{min} }\) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(P\) | 1 | 0,09 | 0,49 |

| \(T_{\text{max} }\) | 0,09 | 1 | 0,62 |

| \(T_{\text{min} }\) | 0,49 | 0,62 | 1 |

We write

\[C = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0.09 & 0.49 \\ 0.09 & 1 & 0.62 \\ 0.49 & 0.62 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]

we then look for eigenvalues and eigenvectors. We find

- \(\lambda_1 = 1,83\quad\) with \(\quad v_1=\begin{pmatrix} 0.46 \\ 0.56 \\ 0.69 \end{pmatrix}\)

- \(\lambda_2 = 0.92\quad\) with \(\quad v_2=\begin{pmatrix} 0.79 \\ -0.61 \\ -0.03 \end{pmatrix}\)

- \(\lambda_3 = 0.25\quad\) with \(\quad v_3=\begin{pmatrix} 0.41 \\ 0.56 \\ -0.72 \end{pmatrix}\)

The Inertia (generalized variance) is given by

\[ \mbox{Total inertia} = \sum \mbox{eigenvalues} \ = 3 \]

| Eigenvalue | Inertia (%) | Inertia Cumul. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\lambda_1\) | 1,83 | 61,17 | 61,17 |

| \(\lambda_2\) | 0,92 | 30,51 | 91,68 |

| \(\lambda_3\) | 0,25 | 8,32 | 100,00 |

Principal components

In order to get the principal components we compute

\[F_1 = X_{cr} v_1 \quad \mbox{ and } \quad F_2 = X_{cr} v_2\]

We get

\[F_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 1,63 \\ -0,45 \\ -0,43 \\ -1,85 \\ 1,96 \\ -0,85 \end{pmatrix} \quad \mbox{ and } \quad F_2 = \begin{pmatrix}-0,81 \\ 1,31 \\ 0,79 \\ -0,12 \\ 0,37 \\ -1,54\end{pmatrix}\] These two vectors form a plane which have \(~92 \%\) of the (generalized) variance. We can represent the indivuals and the variables in this plane with the coorelation circle

| \(\mathrm{F}_1\) | \(\mathrm{F}_2\) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ajaccio | 1,63 | -0,81 |

| Brest | -0,45 | 1,31 |

| Dunkerque | -0,43 | 0,79 |

| Nancy | -1,85 | -0,12 |

| Nice | 1,96 | 0,37 |

| Toulouse | -0,85 | -1,54 |

| \(\mu\) | 0 | 0 |

| \(\sigma^2\) | 1,83 | 0,92 |

\(r(P,F_1) = \mbox{First coordinate of } v_1 \times \sqrt{\lambda_1} = 0.62\)

| \(F_1\) | \(F_2\) | |

|---|---|---|

| \(P\) | \(0,62\) | \(0,76\) |

| \(T_{\text{max} }\) | \(0,76\) | \(-0,59\) |

| \(T_{\min }\) | 0,93 | \(-0,03\) |

Time to look at an example

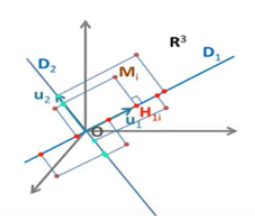

![]() First example of PCA

First example of PCA

Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosawe modify a bit the data for this example :

let’s do the principal component analysis

$names

[1] "sdev" "rotation" "center" "scale" "x"

$class

[1] "prcomp"Standard deviations (1, .., p=4):

[1] 1.7173318 0.9403519 0.3843232 0.1371332

Rotation (n x k) = (4 x 4):

PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

Sepal.Length 0.5147163 -0.39817685 0.7242679 0.2279438

Sepal.Width -0.2926048 -0.91328503 -0.2557463 -0.1220110

Petal.Length 0.5772530 -0.02932037 -0.1755427 -0.7969342

Petal.Width 0.5623421 -0.08065952 -0.6158040 0.5459403we have the principal components

For making biplot need devtools package.

library(ggbiplot)

g <- ggbiplot(pc,

obs.scale = 1,

var.scale = 1,

groups = training$Species,

ellipse = TRUE,

circle = TRUE,

ellipse.prob = 0.68)

g <- g + scale_color_discrete(name = '')

g <- g + theme(legend.direction = 'horizontal',

legend.position = 'top')

g

PC1 explains about 73.7% and PC2 explained about 22.1% of variability.

Arrows are closer to each other indicates the high correlation.

For example correlation between Sepal Width vs other variables is weakly correlated.

Another way interpreting the plot is PC1 is positively correlated with the variables Petal Length, Petal Width, and Sepal Length, and PC1 is negatively correlated with Sepal Width.

PC2 is highly negatively correlated with Sepal Width.

Bi plot is an important tool in PCA to understand what is going on in the dataset.

![]() Hierarchical clustering analysis

Hierarchical clustering analysis

cf. your notes

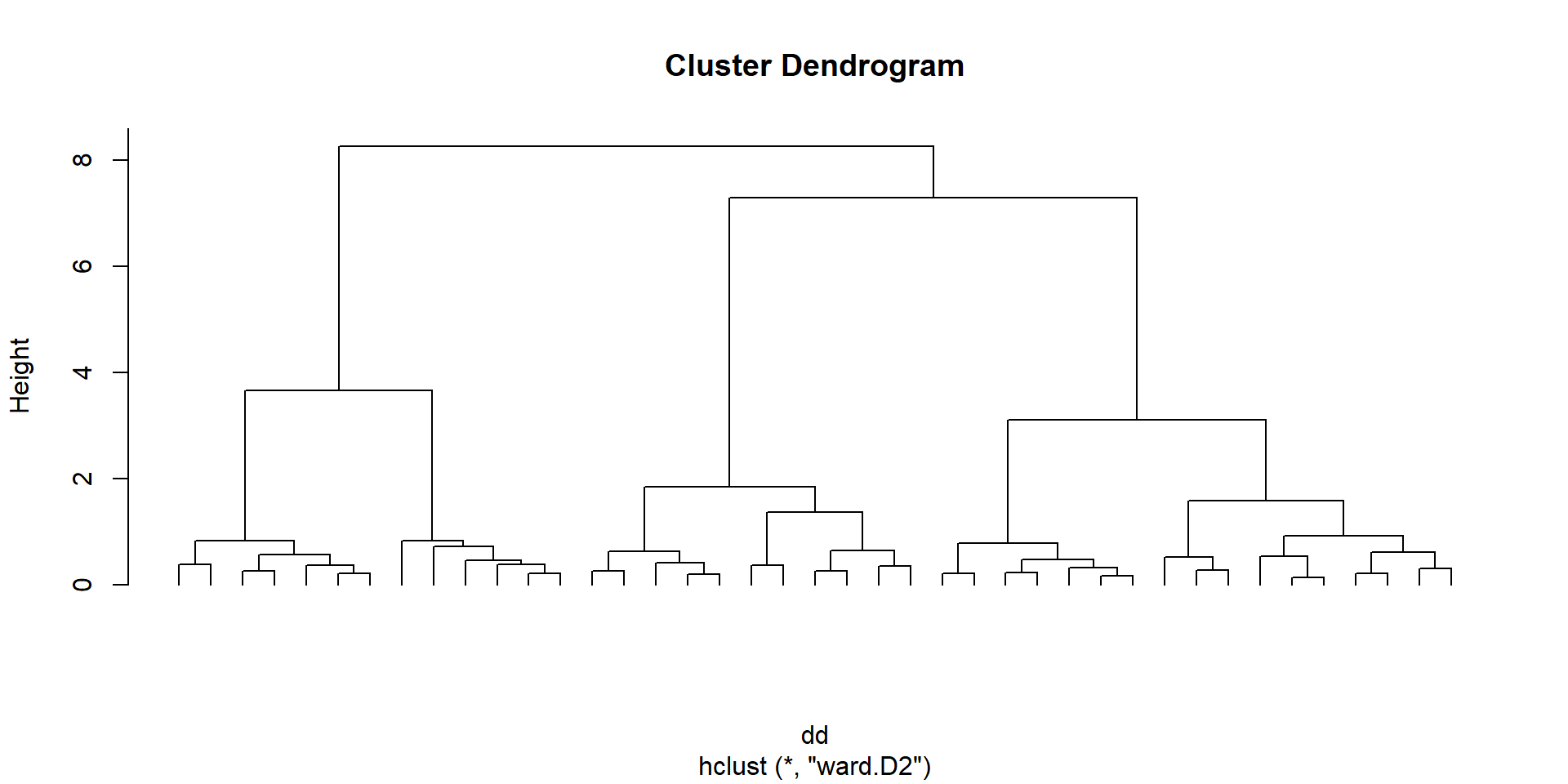

![]() First example of HCA

First example of HCA

we load the required packages

we load the data

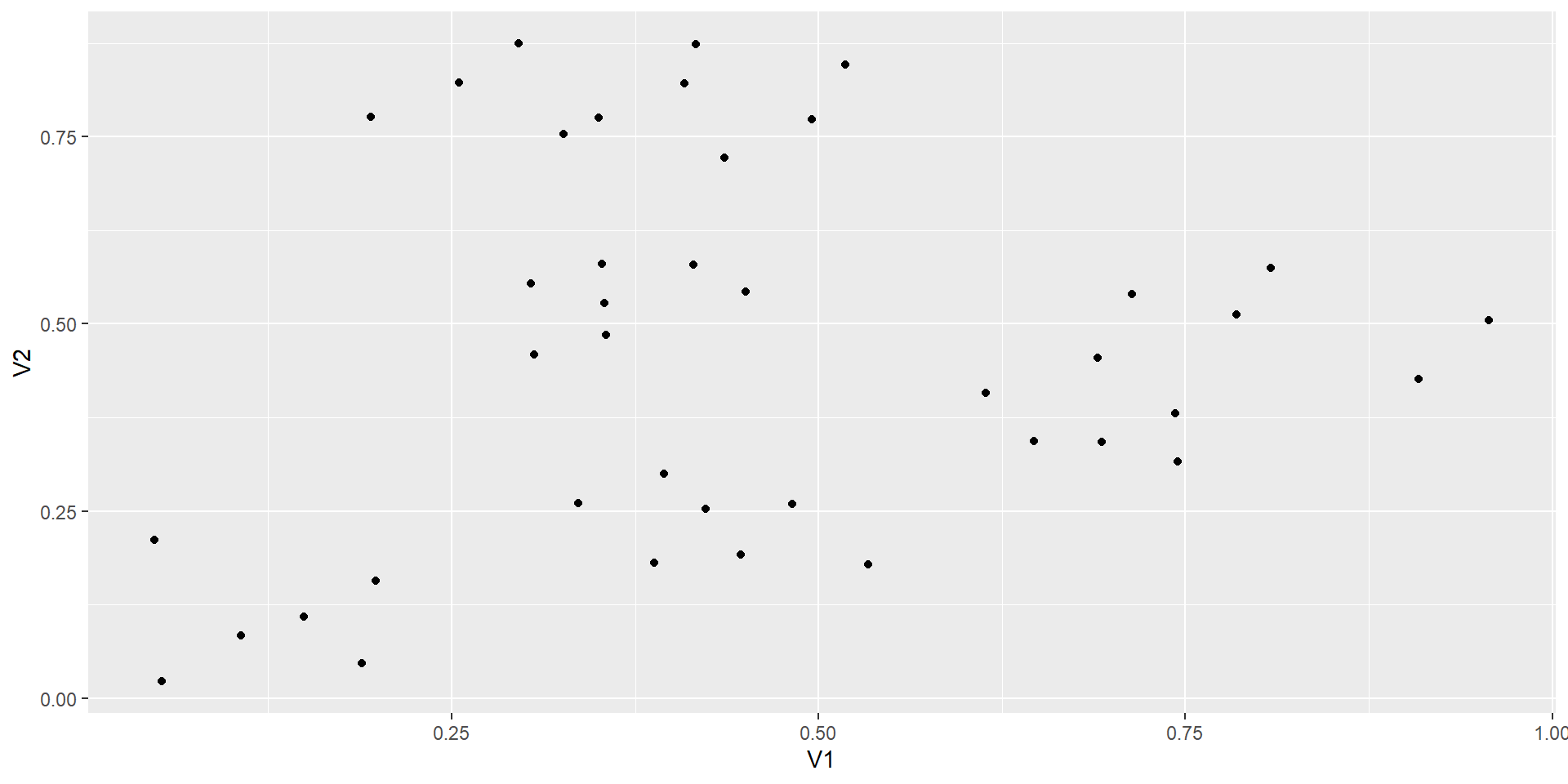

data.cluster = read.csv(file = "data_raw/food-bank.csv",header = FALSE, sep = ",")

head(data.cluster) V1 V2

1 0.04769 0.21150

2 0.05249 0.02238

3 0.10669 0.08343

4 0.14947 0.10921

5 0.18864 0.04716

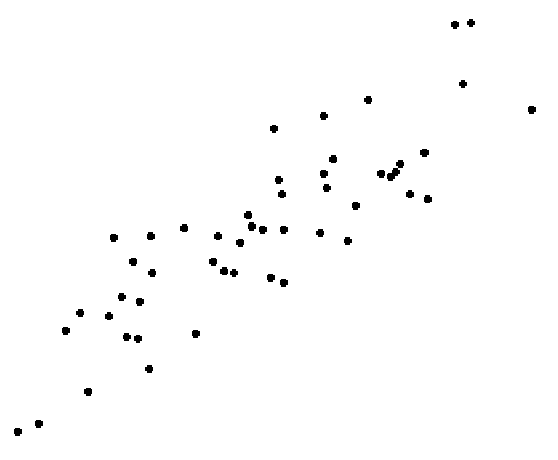

6 0.19818 0.15651we plot the data in the basis (V1,V2)

we want to cluster the coordinates

we define the euclidean distance (it is a choice that makes sense in this case)

with ddwe get the distance between every coodinates.

we can now regroup the coordinates using the ward.D2 method

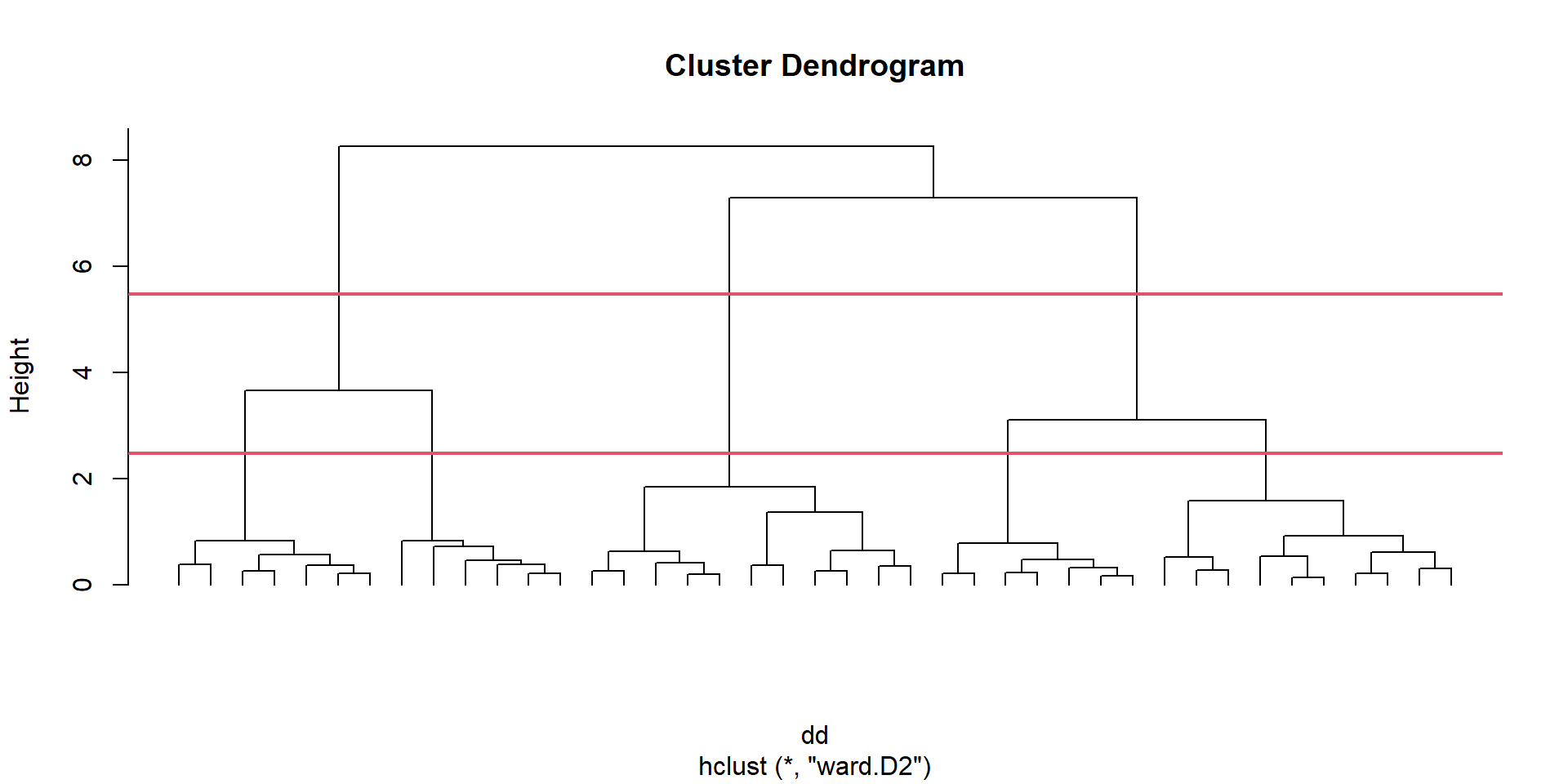

the graph with all the clusters is called a dendogram

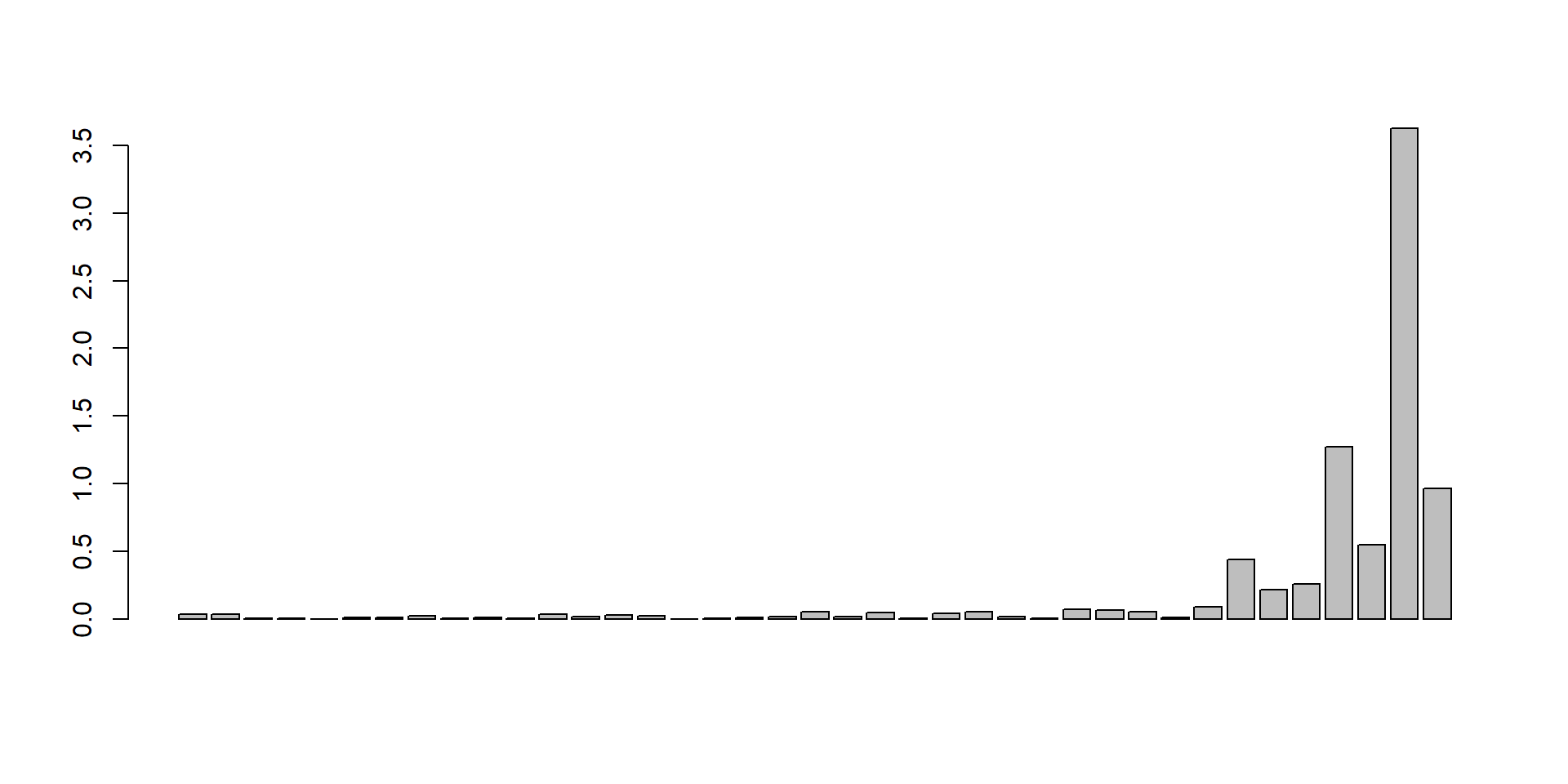

we have to decide where to cut this dendogram to have groups to work with

we plot the heights of this cluster analysis

we will cut the tree at a given number of clusters and obtain the associated cluster for each observation

A brief intro to R and RStudio

A brief intro to R and RStudio